When I was a kid and starting to stray out of the middle-grade section of the bookmobile library, one of my favorite short stories was “The Spook Man” by Al Sarrantonio, in which a carnival of creeps rolls into town and all the parents keep their kids inside. One group of friends who love monster movies and spooky comics, though, sneak out and go to The Spook Man. It doesn’t take long before three of the four have had their fill—but one stays, her true self revealed as a joyous thing of teeth and claws and wild red eyes who joins the traveling haunt.

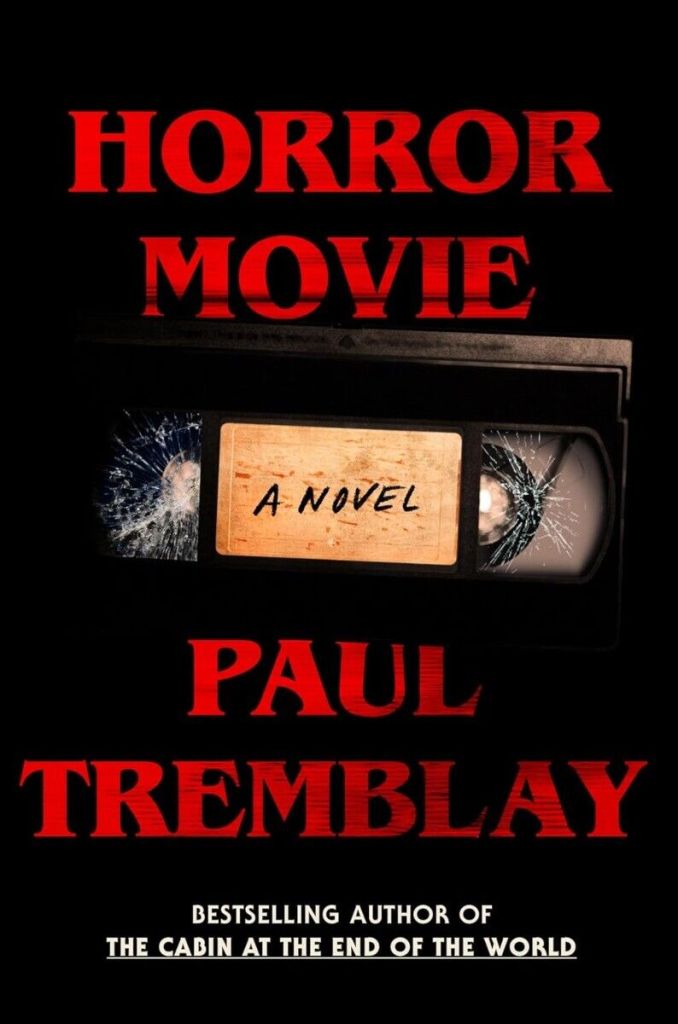

I kept thinking about this story as I read Horror Movie, Paul Tremblay’s latest novel, whose own protagonist enters into a world without knowing enough about it, only to find the darkest, and perhaps truest, version of himself within.

Thirty years after being roped into a low-budget horror film, the narrator of Horror Movie is the only surviving member of the cast. Although the full film was never finished, the release of three clips fifteen years ago have made it into a cult classic, and our narrator how fields offers to reboot and complete the project as the original writer and director would have wanted. But as the last person who knew what that original vision is, it can be hard to take all the “souped-up” visions for the project that irreparably changed our narrator.

With no acting experience, a former classmate had reached out to offer him the role of “The Thin Kid,” a character with only a few lines and no name but upon whose torture and evolution into something no longer quite human the film revolves. The cast and crew were stretched as thin as the budget, and in the intimate and high-stakes environment, the line between the actors and their respective characters blurs. It’s never quite sharpened for The Thin Kid, who bears marks both emotional and physical from the experience. As a new reboot promises the utmost faithfulness to the original—and a reprisal for The Thin Kid’s role—he must confront the events of thirty years ago, and in all the years since.

Besides the low-budget nature of the film, a tragedy on-set only increased the mystique of the clips, and that tragedy is gradually unfolded through the lenses of each of the three threads braided within Horror Movie. Yet it’s clear from The Thin Kid’s recollection that the changes production brought upon him were already in place long before that bloody end. It’s in that change that Tremblay explores the relationship between art and creator, as well as its audience. The Thin Kid becomes his character when the mask is on, but gradually, he becomes more comfortable with it on than without it. The audience is fascinated by the clips, but it’s tough to say how much they’d care if the movie had been completed or wasn’t tied to tragedy. There’s no horror in a vacuum, The Thin Kid seems to be telling us, and the way we ingest and interact with it says as much about us as the content itself.

Tremblay likes his found media, and that’s present here, too, with pages of the old screenplay interspersed with the prose, which itself is taken from the tell-all audiobook being released in advance of the new film. The two forms lend it an air of authenticity, and the unfolding story feels like a peeling back of a curtain. There’s a limitation, or a complication, in that same “authenticity” at the end, which, without spoiling anything, debatably takes “tell all” too far, is exaggerated for hype, or is simply the story told by a man who has fulfilled his mission and no longer cares what happens next.

Whatever the answer, it doesn’t detract from the main questions at the bleeding heart of Horror Movie: Is our face or the mask we wear our true selves? Who are we, really, when the lights are off and no one’s watching? And what’s the dark itch we each try to scratch when we engage in horror?