I love when a historical fiction sweeps me away in an era or sequence of events that didn’t even make the footnotes of my history textbooks but nonetheless needs to be remembered. The genre can be tough, trying to transport the reader to a time and place that might be as foreign as some fantasy kingdom while making it true to what its fictional or fictionalized characters actually encountered, and maintaining the usual things like plot and character besides. When a book does that well, it sings.

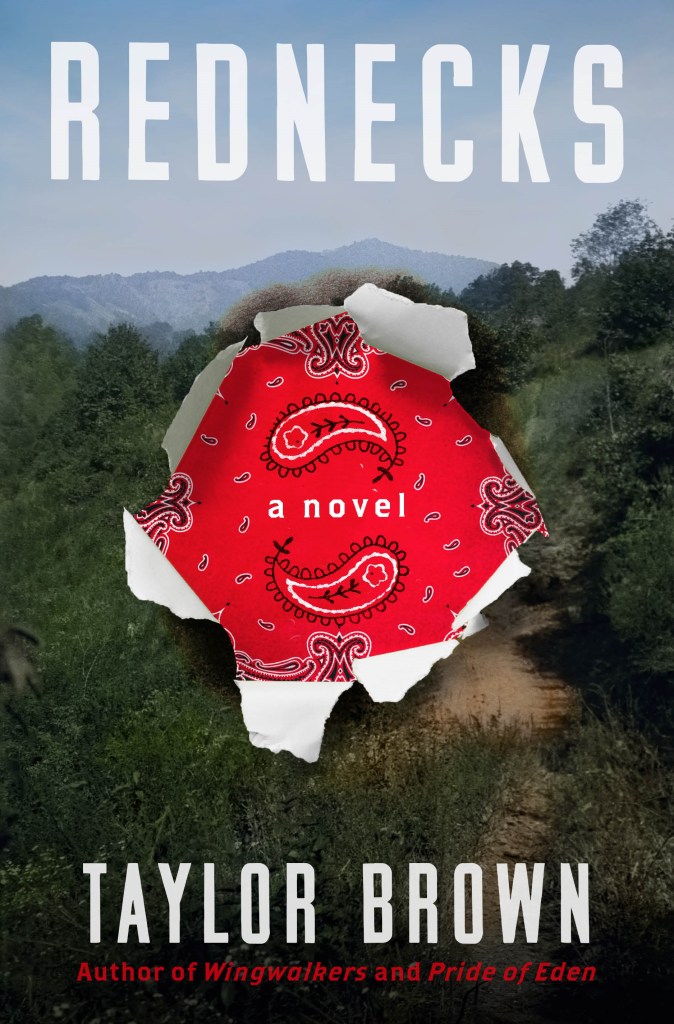

Taylor Brown’s Rednecks does sing, though a little off key.

Between the Great War and the influenza epidemic, the latter years of the 1910s were chaotic, but by the end of the decade, the country was once again chugging toward progress. The engine of that great metaphorical train, though, was hungry for literal coal, and great camps of coal miners in West Virginia were responsible for supplying it. But in an era of company towns, company script, and very few workplace safety laws, wage theft and other abuses soon became unsustainable for the workers and their families, who were often turned out without a penny to their names at the slightest infraction. The thugs coal companies brought in to quell the growing anger turned discontent into violence, leading to an all-out war between workers and their overseers.

The police chief, Sid, tries to keep order as much as he can, while the local doctor, Doc Moo, patches up the men from the injuries sustained on the job and from the thugs’ street justice. Among the workers rise a few leaders, including the indefatigable Frank and Davey Crockett, whose heroism behind a gatling gun soon turns him into as much of a folk hero as his namesake. Meanwhile, legendary labor organizer Mother Jones rallies the men, and tries to protect them by legal means through her wide net of contacts. But the coal companies aren’t giving in without a fight, and it doesn’t take long before the violence spills beyond the coal camps and threatens to become a second civil war.

It was only recently, within the last few years, that I heard of the West Virginia Mine Wars and the origin of the word “redneck,” and I was excited for a deeper and more narrative look at the episode. Brown’s heroes are strong, physically and morally, and the abuses they endure are sometimes difficult to read—though that difficulty is what makes their eventual resistance more satisfying. These are salt-of-the-earth men, and the women in their lives are just as hardy. They are made of the stuff that made America great, and the thuggery can only bruise, not break, that conviction. We know this because of their actions, but also because they tell us this, several times. Very prone to monologuing, these miners.

Meanwhile, the villains are villainous, and the government powers equally apathetic. Their combined treachery is a stark contrast to our heroes, but they’re alike in that neither group strays far from their assigned role. The miners are good and are almost always good, with the exception of one miner threatening Doc Moo when he goes to help the injured from the coal company’s side. That incident, happily, is resolved quickly when a bunch of other miners rally around the good doctor. The bad guys, on the other hand, never have the need or opportunity to see things from the other side’s point of view.

Heroes being heroes and villains being villains isn’t necessarily a problem. It can be a little boring, but it’s not a problem, per se. These are roles, archetypes, that show up throughout countless stories. No one expects Iron Man to accidentally blow up an orphanage because it would be good for his character development, and we’d still side-eye Lex Luthor if he solved global hunger. But by drawing such clear lines between the two groups, Brown only reinforces their disparate natures, and misses an opportunity to tell a story more relevant for our current moment.

Because there are a lot of similarities between the events preceding the West Virginia Mining Wars and today: rising unemployment, depressed wages, unaffordable housing, union busting and gutting, massive corporate power seemingly unchecked by the courts, to name only a very few. Elon Musk is building a whole company town in Texas, as if there wasn’t a good reason we stopped doing those. Part of the issue is the years—decades—of political polarity that reduces the other side as, frankly, evil. Some of the time, that certainly seems to be true. But by and large, this vilification and dismissal of opposing ideas that don’t fit into neat and rigid boxes means even those who find themselves questioning their longstanding political beliefs struggle with leaving the safety of that identity and decamping to that of the “other” they’ve been so convinced is the enemy. It has largely created this moment, and will extend it.

Please don’t mistake me. This is not me dipping into political discourse and saying “both sides” make very good points. More relevant to Rednecks, I am certainly not asking to feel any kinship with the coal companies or anyone fighting for them. But I believe fiction is a powerful thing. It allows us to live a thousand lives, ideally from our comfy couch with our floofy pets and froofy teas. It gives us a glimpse of people who are unlike us in every way, and reminds us that there is more that unites than divides us. It lets us see the good in right choices, and the consequences of bad. I believe in depicting characters as much like people as possible, with all their idiosyncrasies and contradictions. It keeps us from worshipping heroes too devoutly. But it also shows us that bad is a shade of gray—not to diminish the evil the villains do, but to remind ourselves to check ourselves and make sure we haven’t accidentally become the bad guy when we weren’t paying attention.

There’s a fantastic piece of writing advice that says the best villains believe they’re right—that if the narrative lens were positioned a little differently, maybe the reader would, too. Bad guys seldom think they’re bad guys, even if their evil is obvious and destructive. In reinforcing the notion that bad guys are just evil through and through, we remove the possibility that we ourselves could be the villain in someone else’s story. A framework of black and white means we have to ignore the human-ness of heroes, and that anyone calling us wrong must be the opposition—which means if we don’t feel we are the evil one, then the person on the other side of the aisle must be. But when we see evil depicted in a way that we can almost see where they’re coming from, but inwardly insist on choosing another way, we make a virtuous choice. We have seen the temptation, and we have turned down that blessed apple. We have learned from the mistakes of fiction, or of history, or both, so we don’t have to make those mistakes again. We don’t have to subject ourselves to the same tired storylines of evil. We can decide to be better, and build toward the future instead of repeating the past.

Right now, we are repeating the past. This isn’t Brown’s fault, nor is it Brown’s responsibility to fix the unfolding horror of a corrupt administration. But it is a shame that Rednecks, telling a timely and powerful story, chose the easy route of black and white instead of digging in, getting a little dirty, and fulfilling its potential in this crucial moment.