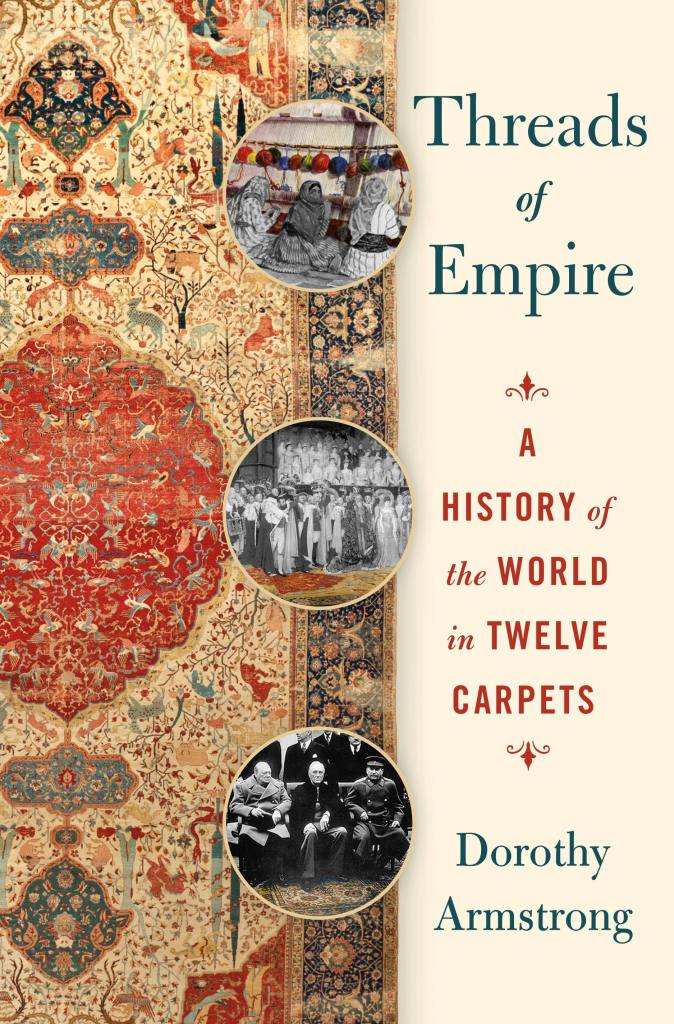

The rug in my dining room was mass produced and bought at a discount store. It’s a purely utilitarian object that I bought and put in my house to keep my dog from slipping on the fake hardwood while he recovered from a sports industry. If the cat barfs on it, fine. If food spills on it, whatever. But as with most things, this kind of ordinary object can carry a real burden of history and importance, some of which are detailed in Dorothy Armstrong’s book Threads of Empire: A History of the World in Twelve Carpets.

Armstrong examines twelve carpets, each woven with great skill and for various purposes. They have their intended uses—horse blanket, carpet, etc.—but most often it’s their second life that brings the most interest. That horse blanket becomes a pawn in the Kremlin’s war for identity (and territory). One highly decorated Iranian carpet is turned into wartime garb for a samurai, and that bit of tailoring tells a saga of trade routes and status. A collection of rugs in an otherwise austere chapel in Eastern Europe provides an odd point of connection between a string of Christian priests and the Muslim women who wove—and interworked signs of their faith into—these objects of practical use and worship alike. There are battles of experts over the authenticity of prized specimens, strategic placements at international peace summits, and enough demand for these relics to spur a flourishing trade of fakes sophisticated enough to stay a half-step ahead of authentication methods.

I love these “biography of things” that take a specific and often overlooked object and delve into what it can tell us about people and civilizations that came before us. In this case, the things we place beneath our feet, or under our knees, or between our horse and saddle. Most of the rugs discussed come from the same general area of the world, though the regions where the portions of their respective stories ultimately take place are much more scattered, as are the times in which they were created. The ways these practical objects are turned into trophies, too, is intriguingly multifaceted.

One thing sometimes lost in the discussion about objects and the things they tell us about a long-ago group of people is the individual or individuals who actually made them. For the most part, Armstrong points out, this has been lost to history—not just because of the length of time but also because, to our knowledge, they were skilled but poor, and/or—far worse for the historical record—women. There are few resources to fill in the gaps on who the individual weavers, of course; in some cases, they lived and died millennia ago. Armstrong attempts to fill that gap with suppositions about their lives based on the records we have about what life was like around that time and around that place. While those attempts weren’t enough for me to feel I had a firm grasp on the time or place, but it did succeed in making me wonder about the hands that made the rugs in question on an individual level. Isn’t imagination the first step to knowing someone? Wondering about their aching bones and the muscle memory that made animals and scenes of adventure appear out of knots and string?

That wondering is the thing that reveals—if not a weakness, then an oversight, or a preference not clearly explained in the front matter. Armstrong writes that her survey is obviously incapable of producing a thorough history of carpets or their makers or the people who have paid in fortune or blood to take possession of them. This is, after all, an “episodic and eclectic” survey of objects and history and power. Though the stories span the world, the origin of each carpet seems to come from a relatively small part of the world. Undoubtedly, the Middle East isn’t the only creche for carpet artistry; I’d be interested in the origins of rugs from other regions, and how their legacies have endured. (And this is, as the subtitle tells us, the history of the world in twelve carpets!) Then again, there’s a reason “Persian rug” carries such a reputation even today. And perhaps it’s flattery for Armstrong that her work has left this reader wanting more.