I read Kate Lebo’s The Book of Difficult Fruit while trying to pickle, dehydrate, bottle, jam, and sauce my way out of a delicious deluge of produce. I’m fortunate to have it come my way most late summers and early falls, but every year, as I’m cutting open yet another apple to find yet another live worm trying to inch across my cutting board to freedom, I wonder how I got myself into this mess again. I look forward to it before it comes and I’ll appreciate it after, but in the moment, it feels overwhelming, and I understand why many people think fruit trees are too much fuss to begin with.

“But why do we let our fruit become a nuisance in the first place?” Lebo writes. “Because so many of us are accustomed to buying fruit pest-free, in easily handled quantities, from twenty-four-hour supermarkets? Or do we decide this is not the thing we need, all this fruit and the care of the fruit and the eating of the fruit we cared for, the entrapment of all this nurturing?”

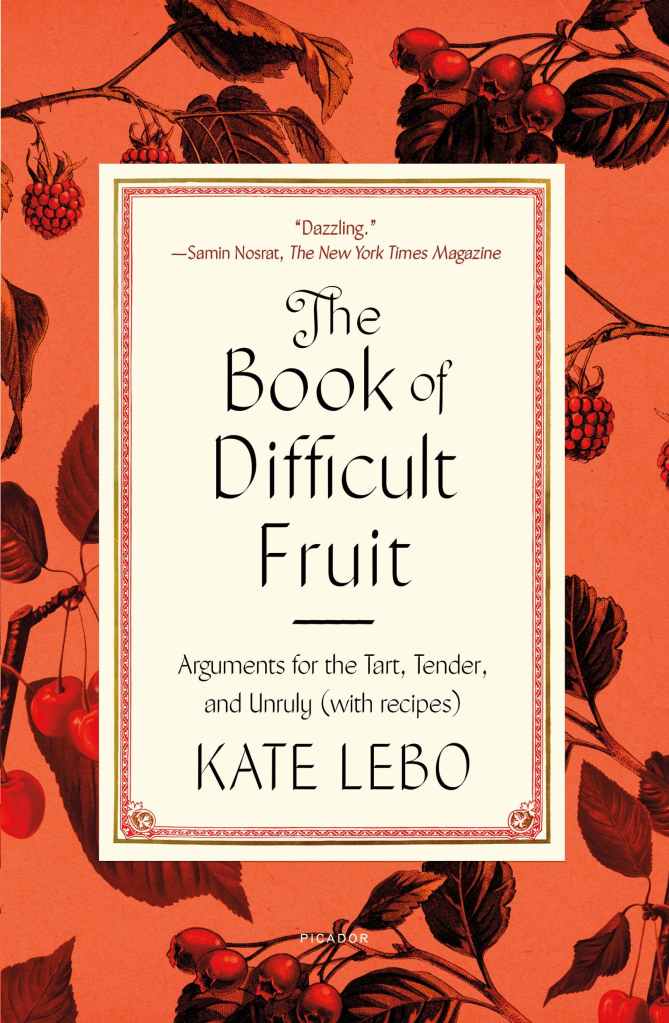

Lebo muses about this and other questions of food, convenience, and our connection with the earth and the things it produces in The Book of Difficult Fruit: Arguments for the Tart, Tender, and Unruly (with recipes). For each letter of the alphabet, Lebo considers a different food item, but this is no “A is for Apple” offering—in this case, A is for Aronia, also known as chokeberry. What do you make with aronia? An antioxidant-packed smoothie, or a dye for paper and cloth. There are familiar fruits here—blackberry, cherry, kiwi, pomegranate, rhubarb, zucchini—but many offer an educational experience just by learning they exist. Thimbleberry. Osage orange. Faceclock. Medlar. Some are hard to pick, while others are hard to grow, and others still are just plain hard to know what to do anything with. Lebo loves them all.

Interwoven with each is Lebo’s introduction or interaction with the item in question. For vanilla, she considers the sway vanilla-scented lotion held on her adolescent social group. For juniper berry, Lebo prods the historical use of the fruit as an abortifacient and period regulator, as well as Lebo helping a friend through an abortion. A few chapters swirl around old lovers and family secrets. Sometimes, Lebo gets pretty personal, while other times her tone remains breezy and curious. It works as a sometimes meandering but never unpleasant series of thoughts on things most people give no thought to at all. I won’t be making most of these recipes—Lebo couldn’t even find ume plum, where am I supposed to get it?—but their value is in proving the use of these unthought-of things. And because there is no throughline or plot, per se, The Book of Difficult Fruit works as a book you can pick up, say, while waiting for a batch of jars to finish canning.

There is one nagging detail that has kept me from fully savoring the memory of The Book of Difficult Fruit. She refers to exes only by an initial, and more than one chapter features W. But here, W demands “elaborate meals I loved to make…Then he required everything wheat-free, soy-free, corn-free”; there, W has celiac disease. These aren’t necessarily incompatible, I suppose, though the revelation of the second makes the framing of his avoidance of wheat in the first a little unsympathetic. But here, Lebo leaves him by stashing a suitcase in the trunk of her car and leaving while he’s gone; there, he leaves her because she won’t stop baking with wheat flour, and after she’s sure he’s gone she throws flour around the kitchen. I suppose she could have left him and then come back. I suppose she could have dated more than one wheat-avoidant man in Seattle with a name starting with W. Maybe it’s just a little artistic license, but where’s the faith in the reader to say, “Hold up.”

While this detail is unrelated to any load-bearing part of the narrative, it does make me question the clarity, at best, and the truthfulness, at worst, of the personal editorializations woven throughout Lebo’s musings on the produce that surrounds us. The produce is the point, not cancer scares or teenage lunches with Mom, but it also seems odd that the author and publisher would think her musings are so unimportant. Maybe, in that way, The Book of Difficult Fruit is like many of its subjects: good, but a little complicated to consider at the same time.