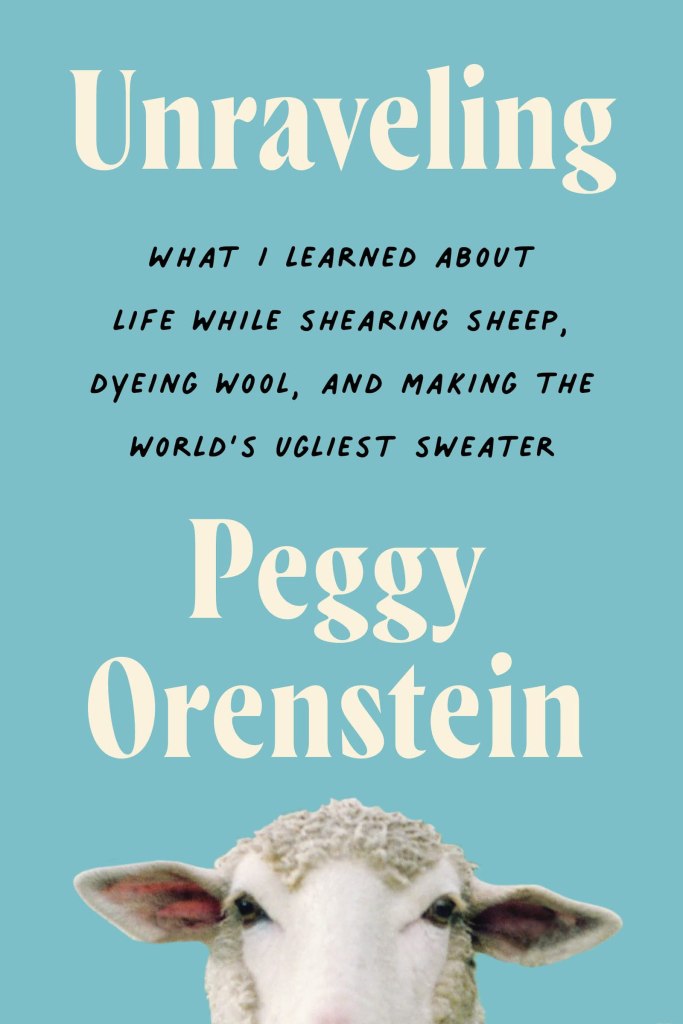

Like a lot of us these days, I’ve been trying to pay more attention to the things I consume. It’s almost impossible to avoid single-use plastics or things made in sweatshops, but, you know. I try. Although it feels like I’m thinking a lot about the everyday foods and objects that surround me lately, it turns out I haven’t been thinking nearly enough—not compared to the lengths Peggy Orenstein goes to in her book Unraveled: What I Learned About Life While Shearing Sheep, Dyeing Wool, and Making the World’s Ugliest Sweater.

As the world was shutting down in the early days of COVID, Orenstein, unsettled and overwhelmed with worry, came up with a project to keep herself busy. Nothing unique about that, except that her project was to make herself a sweater from scratch—meaning not just from yarn, but from the wool that yarn would be made of. From learning to sheer a sheep, to cleaning and carding the wool, to spinning the wool into yarn, dying that yarn, and finally actually knitting, Orenstein did it all. (At one point, she does remark that she should have stuck with sourdough.) The result is a lumpy, boxy sweater more valuable for the experience of making it than aesthetically pleasing. But the length of that process, and how laborious and skilled each step within it was, made her appreciate every lumpy inch of that sweater.

Some of the steps are fairly self-evident. Of course you need to clean the wool. Of course you need to dye it if you want it to be a certain color. I remembered the need for cleaning wool, and the bit about it being coated in lanolin, from an elementary-school field trip. Orenstein, too, is fairly well-versed in the general sheep thing from the outset. Still, there were plenty of surprises, such as just how hard it would be to clean that wool, or how slippery sheep—and lanolin—can be. Yet each obstacle is merely a challenge for Orenstein, who faces them not in a rah-rah sense but with a little good-natured self-deprecation. That attitude helps make each step, and misstep, feel more like a fascinating conversation than a staid travelogue or sermon.

But Unraveling is also a pandemic project, and there is no avoiding the atmosphere that surrounds every step. Orenstein worries about her elderly father, with whom she can gratefully see over video chat but is unsure if she’ll be able to see him again—and if his failing memory will outlast the pandemic. She also worries about her daughter preparing to go to college in the midst of the pandemic, leaving Orenstein and her husband empty-nesters. Family concerns continue as Orenstein meets people in the course of her project, and how the overwhelming majority of them learned fiber arts from their mothers—so much so that Orenstein creates her own shorthand (SLFHM) when that commonality arises. Orenstein’s relationship with her own (late) mother wasn’t always tidy, and a love for knitting sometimes seemed like the only common thing between them, so this project also forced Orenstein to grapple with some of those more complicated parts of that relationship.

Though these more emotional parts of Unraveling are thoughtfully wrought, the light tone persists, and so does Orenstein’s focus on the prize: the ugliest and most expensive sweater she’s ever made. At the start of the book, such a thing hardly feels like a prize; by the end, we all get the satisfaction of a job well done. And with each part of the project, and each new ray of light shed on some previously invisible part of our world, that ugly sweater becomes dearer still.