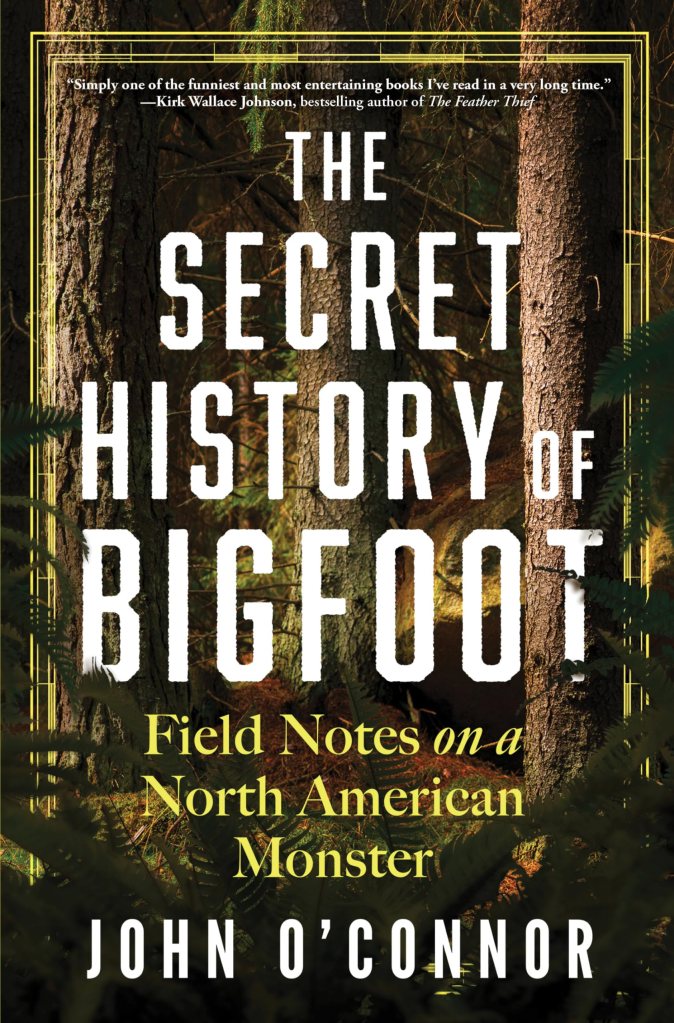

For the last several decades, the story of a creature that may or may not walk in the densest forests North America has to offer has captivated millions. Whether Bigfoot is actually real or not, though, is less important than the belief and infrastructure built up around the stories, argues author John O’Connell in The Secret History of Bigfoot: Field Notes on a North American Monster.

Part of the fascination behind the story of Bigfoot—or Sasquatch, or whatever you want to call it—is that it is both ancient and new. O’Connell traces the roots of the story to an array of stories told by various indigenous tribes both in North America and abroad. At the same time, the modern legend as most of us know it is younger than the automobile. That hasn’t stopped it from proliferating around the country and infiltrating popular culture.

There’s been a lot written and speculated about whether Bigfoot is real, per se. While O’Connell does touch on the theories and attempts to find incontrovertible truth about some undocumented creature stalking the forests of North America, his broader focus is on the effect Bigfoot has had on people, not only culturally but individually, as well. It’s the latter that I found particularly interesting in The Secret History. Believing in Bigfoot isn’t something reserved for a certain kind of person. O’Connell meets MAGA-devotees and environmentalists, devout faithful and atheists, well-educated and dropouts—all of them believers in an ape-like creature shrouded in shadow. Though their differences would mean a gulf lies between them in other circumstances, this common ground joins them more tightly than most shared beliefs might; holding fervent belief in Bigfoot, after all, tends to alienate a person from society at large. There’s power to be had in uniting as outcasts.

And they say our country is hopelessly divided.

Throughout the novel, O’Connell’s tone is light, often joking. For the most part, this helps move the book along (though I’m not sure how many “Harry and the Hendersons” references we really needed), and he does manage to keep his toe on this side of the line between lighthearted and mocking. He seems genuinely earnest and curious in his inquiry, and that helps bridge a different kind of divide. It’s easy for those of us on the outside of the cryptid believers to take Bigfoot stories so unseriously that even a grain of salt feels generous. Yet The Secret History was thought provoking nonetheless. Even if I haven’t come away from this book believing in Sasquatch any more than I did going in, I have a far greater belief in the very real place, and effect, these stories have in our world.