There’s a spare charm to the minimalist work of Estonian composer Arvo Pärt, one that Hollywood has lately made use of in hits like 2013’s Gravity. As with most art that seems simple, its innerworkings are far more complex. But the journey its maker made to write it is even more complicated, and interesting. That journey is told in Between Two Sounds, a graphic novel translated from the original 2018 Estonian publication.

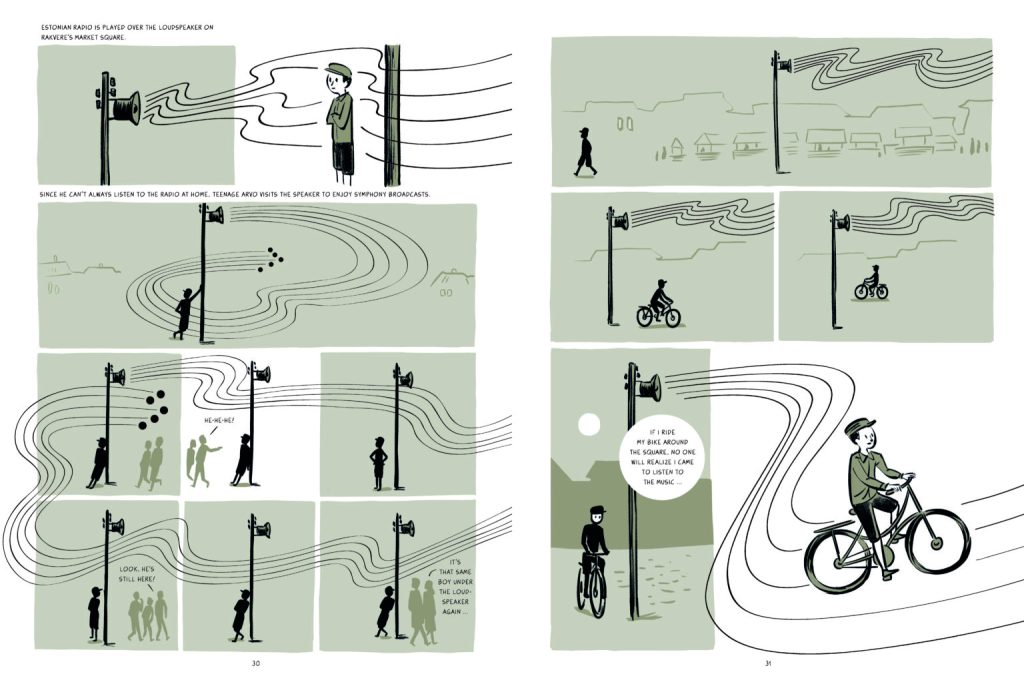

The pursuit of sound stirs little Arvo as he plinks away at the family’s piano that mostly works. There are more sounds than just the notes on the piano, and he begins noticing all kinds of music. His mother enrolls him in a new children’s music academy, and he is immediately smitten with his new lessons—though all the improvising and mimicking other music he hears leaves little time for practicing the pieces and exercises he’s assigned. Recorded music is hard to come by in the Soviet Union, especially during the 1940s and 50s, so he spends hours standing by—or riding his bike around—the symphonies broadcast from the speaker in the town square. He moves beyond piano to gain proficiency in all manner of instruments, and he’s good enough at playing that teachers of other subjects give him a pass when he daydreams or otherwise does poorly in their classes.

It’s no surprise to anyone that Arvo enters a music conservatory, and they, too, are impressed with his obvious gift for music of all types. The conservatory’s library of music from all around the world expands his horizons, and he sees new opportunities in his own craft. Those visions only expand as he begins working at a radio station. He begins pushing boundaries, dipping a toe, and then a foot, and then a step, into avant garde. Being a creative of any stripe in the Soviet Union, however, means treading a fine line between national pride and violating the nebulous ideals of the party, and Arvo pokes the proverbial bear even more when he begins to incorporate his growing Christian faith into his work. His popularity in Estonia and throughout the Soviet Union helps shield him for a time, as does his flawless artistic execution. But the iron curtain is heavy, and Arvo seems incapable of listening to reason, or anyone or anything that isn’t the musical drive within him. He can only outrun the censors for so long, and then where will he go? Where will he be forced to go?

I’ve been familiar with Arvo’s work since my uncle slipped me a CD of Arvo’s work, including the enchanting Spiegel im Spiegel. I’ve been less familiar with the man behind the sounds I’ve loved, and completely ignorant of how deeply he wove his faith into his compositions. He’s not alone in that, of course; much of the early European music that’s lingered was driven heavily by liturgical use and inspiration. But Arvo’s story departs from those older inspirations in a few ways, not least among them that the regime he lived under made it dangerous to promote this kind of religiosity—but that his popularity largely protected him despite it for decades. Such popularity continuing, and that popularity being enough for government officials to look the other way, was by no means guaranteed, making Arvo’s work a brave or stupid thing, indeed. In creative work, the line between those two is sometimes paper thin. Perhaps more interesting still is that Arvo’s creative rebellion isn’t intentional as such, but rather a passive thing as he devotes virtually all his time and energy to his craft.

In that way, Between Two Sounds is a story of devotion as shown through multiple lenses. There’s Arvo’s devotion to music, to his faith, and to perfect one to express the other; there is the surface-level devotion to the Soviet Union that everyone around him has to adopt, if for no other reason than to maintain a protective veil of patriotism; and the zealous devotion the Soviet Union expects each and every one of its citizens to have. This is not a story of the Soviet Union versus Arvo Pärt, but about an authoritarian regime demanding performative patriotism against those who have far more interesting things to think about. Arvo, like many others, does eventually catch the wrong kind of attention. He loses, in the sense that he has to leave home or risk dire consequences for himself and his family. Yet it’s clear at every point in Arvo’s life and journey that this is a much lighter punishment than compromising his art for physical safety.

In the beginning, before we even meet little Arvo, we see the adult version of the composer traveling upon the long tail of a note wondering how long his journey to the creation of his music will be. “It seems this road to Golgotha will last an eternity,” he says. By the end, we do see just where he’s ended up—musically, but also with his impact on listeners, even those primed to reject him as he’s evicted from his homeland. Thinking about that theme, it’s rewarding, even if narratively the end of Between Two Sounds feels rushed, with its last-page summary of his exile and the latter decades of his life a taped-on coda to an otherwise tightly written melody. But Arvo is still alive, coming up on his 90th birthday, and back in his native Estonia. Between Two Sounds is, in addition to its other merits, a lovely tribute, and I hope its subject can see an inkling of the footprints he has left behind him in nearly a century of creation.