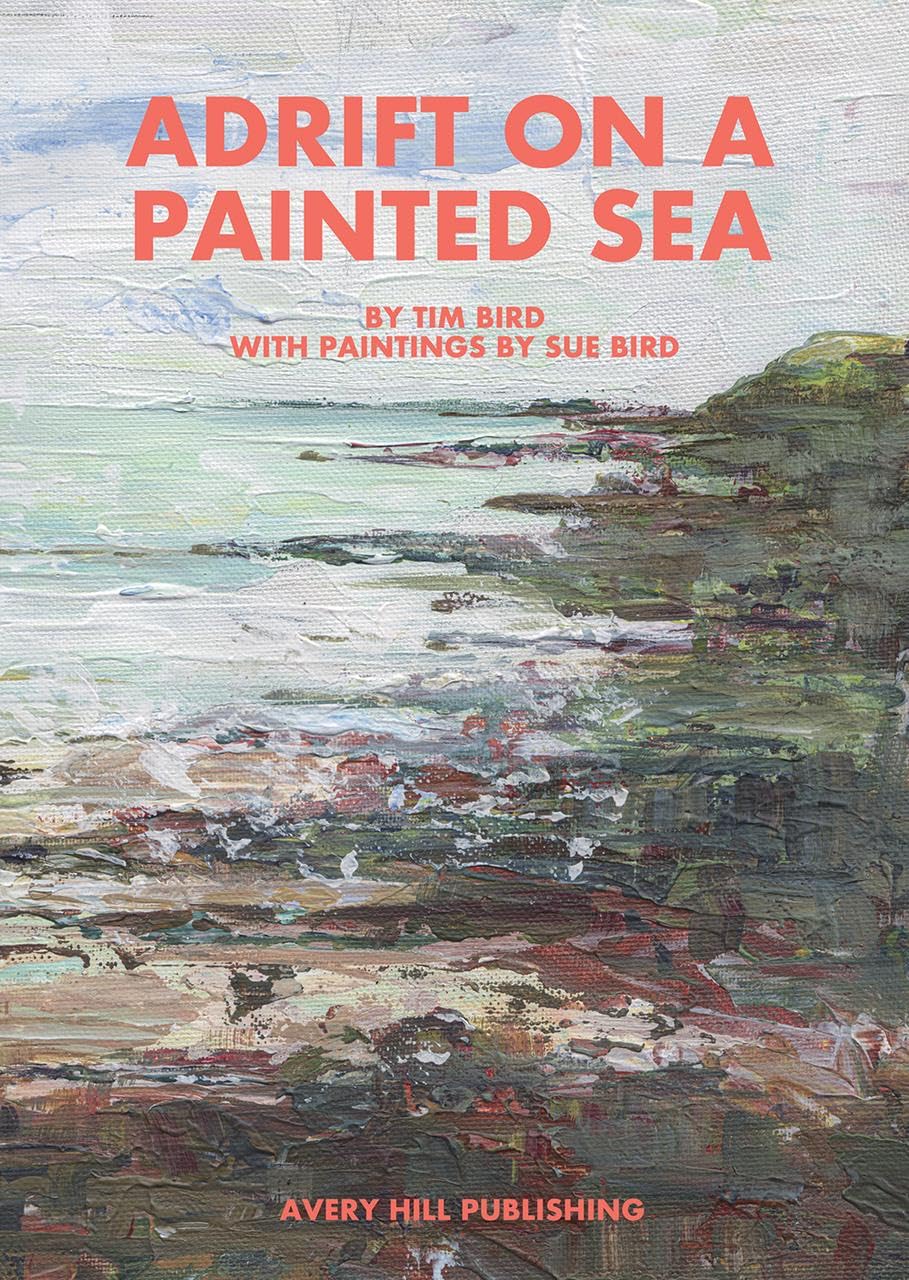

No matter how well you know a person, it’s a fact of life that you’ll never know everything about them. Though this constant discovery might be part of the magic of knowing another human being, its continuance after death means having to reconsider something about the person who’s gone. Tim Bird explores this in his graphic memoir, Adrift on a Painted Sea, which features his late mother’s paintings.

The works Tim Bird’s mother painted were always part of his life, fixtures on walls and in closets to the extent they were almost unnoticed through their normalcy. Although he did sometimes talk with his mother about her work, it wasn’t until late in her life, and after her death of cancer in the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, that he began to wonder more about her work and the part of her that drove that creation. In pages that switch from his cartoons to her paintings, Bird reminisces about his mother, her work, and the influence she’s had on him as an artist and a parent.

Adrift is a story about getting to know another part of someone after they’ve passed on, about discovering more about someone you thought you knew through and through and being unable to ask them about it. In Bird’s case, the questions aren’t earth-shattering, but they are a sharp memory of the still-recent loss of his mother. Every question a deceased loved one can’t answer, after all, is another reminder that they’re gone. And the discovery, along with the new perspectives granted in hindsight and adulthood, leads to more questions about other facets of his mother’s history and world—questions that, of course, she can’t answer.

But Adrift isn’t a quest for new truth or understanding; rather, it’s a story of Bird’s reflection about his mother and the stunted sort of goodbye that too many experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. With a sprinkling throughout of “found” media, like a letter announcing her work’s inclusion in a youth art show, the full program for that show, and pages from a book his mother had loved when she was young, we are silent observers as Bird grieves in anticipation, then grieves in loss.

Beneath that strong current, though, is a message about art Bird’s mother would likely have liked far better than ruminations about her loss. She was dedicated to her art and diligent in her craft but rarely parted with or publicized her work. For Sue Bird, the creation of art, and her practice of it, was enough purpose in itself. It was only with the advent of Instagram and the urging of her son that her work met an audience outside of her four walls. With so many of her works incorporated in this book, perhaps it is finding an even wider audience yet, even after her passing.