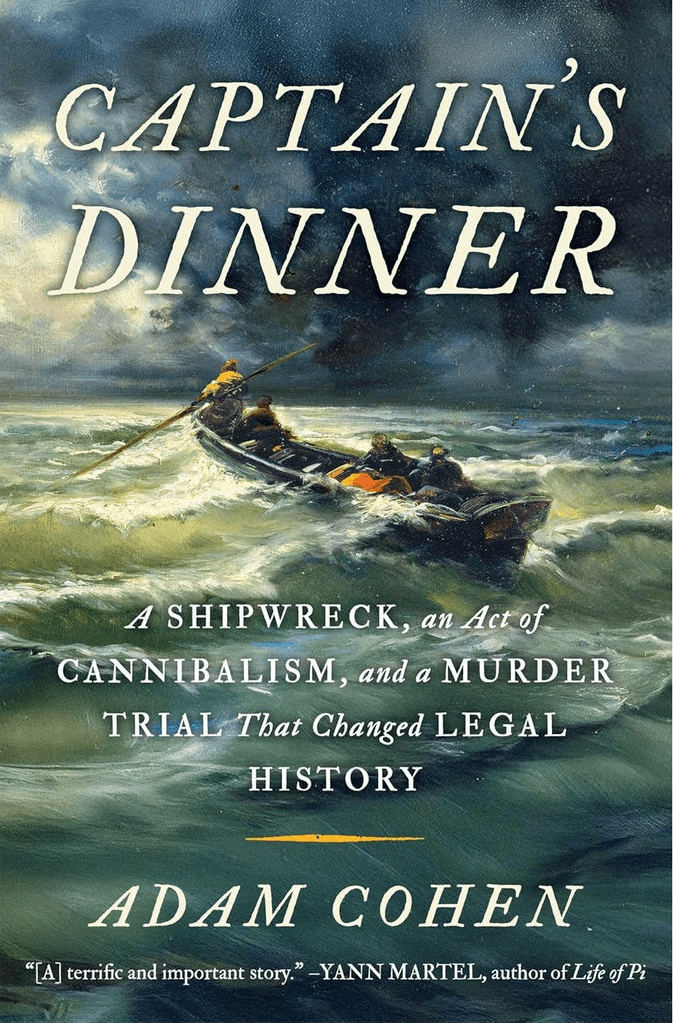

There’s a delicacy in writing about history. For one thing, having the benefit of knowing the end of a series of events from the beginning makes it easy for us to criticize the actions of those who lived it. It can be tricky, too, to not overlay the norms and expectations of today to those in the past. Adam Cohen treads that line carefully in his latest, Captain’s Dinner: A Shipwreck, An Act of Cannibalism, and a Murder Trial That Changed Legal History.

In 1884, as the age of sailing wanes, Captain Thomas Dudley gets a gig sailing a yacht, the Mignonette, from England to Australia for a wealthy client. But a captain’s nothing without a crew, so he sets out to recruit one. His first few hires fall through (no warning sign there, surely!), but he eventually ends up with an experienced sailor and navigator, Edmund Brooks and Edwin Stephens, respectively, and a 17-year-old cabin boy, Richard Parker. At first, things are going well and the little ship is making good time. That changes abruptly when a storm rolls in and quickly sinks the Mignonette, giving the crew just minutes to grab supplies and make for the dinghy. In those minutes, all four managed to get out, but managed to grab only two tins of turnips as provisions.

After nearly three weeks of virtually nothing to eat or drink, Dudley invokes the “custom of the sea,” in which lots are drawn to determine who will be sacrificed for the good of the others. Brooks refuses to participate. When Parker drinks seawater in desperation and falls ill, Dudley and Stephens take the matter into their own hands. Four days later, the boat is rescued. Grisly though this voyage turned out to be, Dudley and his surviving crew return to England anticipating the worst to be an investigation into whether it was human error that led to the sinking of the Mignonette. Unfortunately, as Cohen writes, 1884 happens to be a bad year to participate in what was rapidly becoming seen as an antiquated and barbaric practice. The three are instead arrested and tried for murder. The result of those legal proceedings still reverberates in law schools and court rooms today.

The story itself is one of those treacherous and lurid tales of exploration that’s hard to look away from, and that’s even before you get to the cannibalism. (If you want to know more before committing to a whole book, the podcast Criminal recently had an episode about it.) The gruesome details are what made it stand out in a Victorian world filled with penny dreadfuls and salacious murders, but the courtroom drama is a story about what happens when public opinion begins to shift, and when the levers of change are pulled without notifying those far away from places of power.

Within the march of social reform during the Victorian era, both the legal landscape and public opinion were growing more aware, and concerned, about the unequal balance of power among leaders of industry and those who were on the payroll, as Cohen writes. Even the way the country was thinking about its empire and its treatment of the people it subjugated around the world was softening, in a sense. “All of this,” he writes, “arguably made 1884 the worst year in history to be an English cannibal.” And while the feelings of the common man may have been more sympathetic to the plight of those who survived the sinking of the Mignonette, those within the legal system were keenly aware of their opportunity to set legal precedent. And set it they did.

There’s a bit of a tonal shift between the end of the story and Cohen’s afterword. Throughout the tale of the voyage, the wreck, the rescue, and the trial, Cohen maintained such an even tone that even as a reader I got to really feel the conflict of competing ethics. On the one hand, Dudley didn’t follow the proper procedure of the “custom of the sea,” and even if he did, he still killed the boy just four days before they were rescued. On the other, the captain couldn’t have known they’d be rescued, and did seem to act within the bounds of his knowledge of biology and cultural practices. A not insignificant factor, too, is how delirious all four of them must have been under such conditions for so long, and how desperate. When Cohen speaks, though, seemingly less restrained in his afterword, his opinion is far less measured. So different is his opinion and tone from the measured presentation of the facts that it was almost jarring.

For example, in the narrative, Cohen describes the actions one judge took to steer the jury’s decision in a way that allowed him alone to set a new legal standard; in the afterword, that previous blatant strong-arming is framed as heroism, the judge now “coming to the defense of everyone at the bottom of a social hierarchy.” While I found I couldn’t disagree with his conclusions, the stark difference in tone did make me want to challenge them. Yet within that gap between how we were shown the legal proceedings and how we were told to view them in the afterword’s retrospect is the evidence that Cohen did take great, and successful, pains to remove his opinion from the narrative itself, allowing us, at least for a time, to come to our own conclusions about the cannibals from the Mignonette.