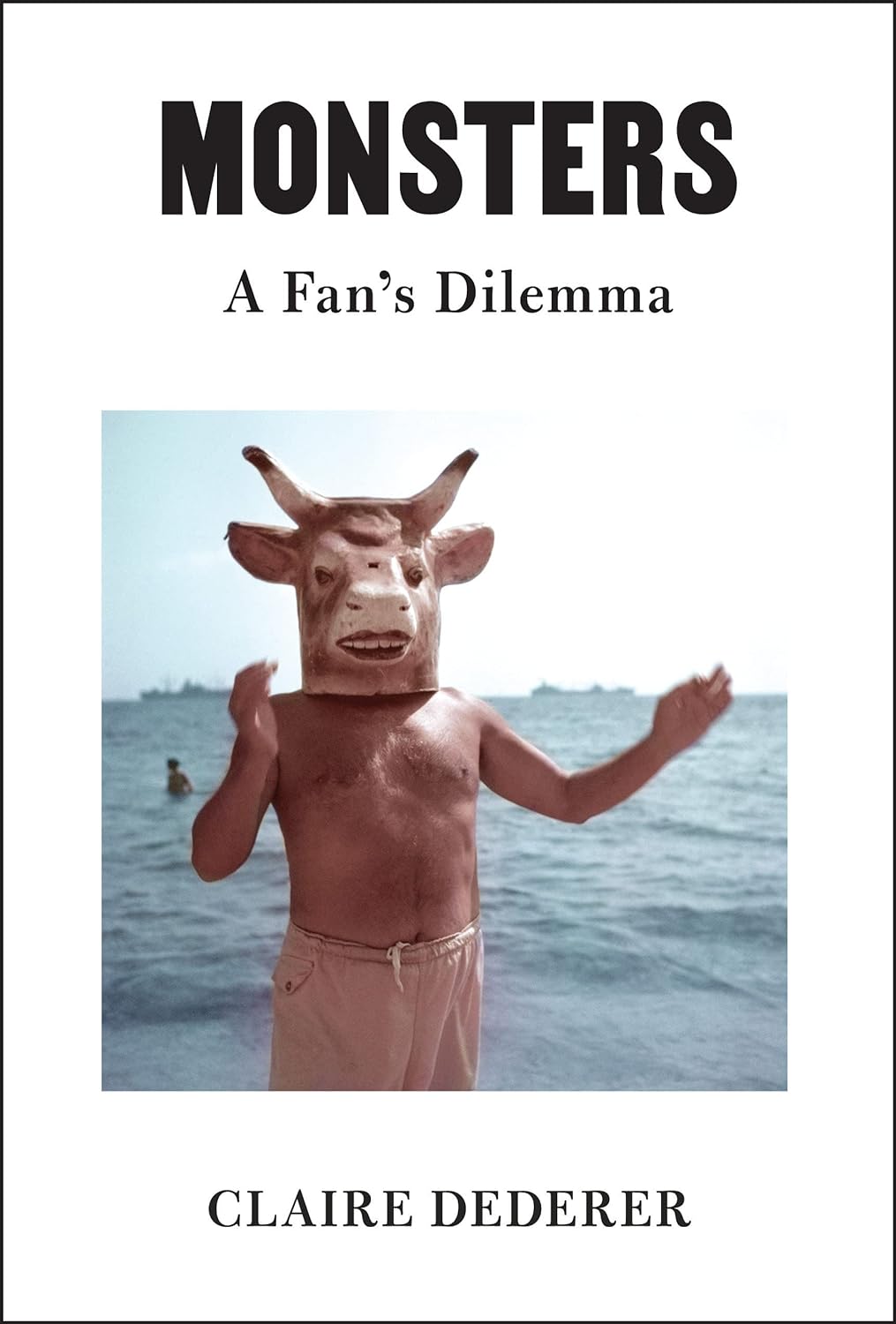

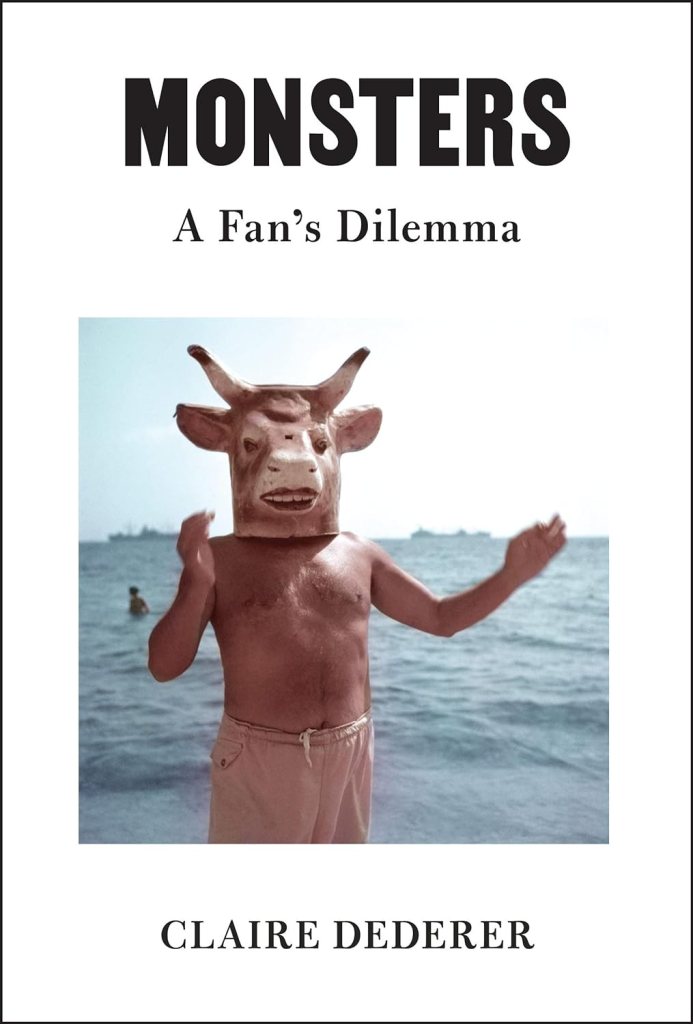

During the last several years, a lot of celebrity skeletons have been yanked out of the proverbial closet, and, though reactions tend to be mixed, the overall trend has been pretty negative for the owners of these skeletons and closets. Much could and is said about the nature of “cancel culture,” but Claire Dederer’s Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma is more concerned with how we look at the art these accused, and sometimes convicted, have made.

Over the span of 288 pages, Dederer muses about celebrities from Harvey Weinstein to Virginia Woolf and from offenses from pedophilia to racism, though most of the subjects of her consideration are male and most have committed offenses within the realm of sexual assault. Though there, too, is some delineation. Weinstein coercing starlets to perform sexual acts or Woody Allen’s incestuous pedophilia with his underage stepdaughter are here in a different class from David Bowie’s romancing a teenage girl who even today regrets nothing of that encounter.

If ranking these kinds of misdeeds feels uncomfortable, that’s kind of the point. There can be no judgement, after all, without deciding where the line between permissible and canceled falls, and why it nabs, for example, Bill Cosby but spares Donald Trump. Why some are allowed to hold repugnant ideas under the banner of “products of their time,” despite those ideas not being acceptable at the time, either? (A question not directly asked but this inquiring mind wants to know: Did any of the Varsity Blues scandal people really get canceled? Why not? Has anyone been canceled for, say, tax evasion yet?)

There are few, if any, answers in Monsters, but Dederer’s argument ultimately asks us to reflect upon our own values as well as our judgement. This plea is stronger sometimes than others; when asking her audience to consider their own array of foibles, it’s hard to compare, say, telling white lies or being judgy with rape, statutory or otherwise. Discussing Woody Allen with a male colleague who seems baffled that Manhattan might be viewed differently in light of the allegations against Allen feels like the start of a conversation that never concludes. In considering another of Allen’s works, Dederer’s own overall conclusion seems to be, “Well, whatever, I still love Annie Hall.” It’s here, I feel, that Monsters has its greatest omission. Maybe Annie Hall is still great art; maybe Roman Polanski’s work is still groundbreaking. In many cases, I can see an argument for separating the creator from the art–the product from a multi-faceted maker who, away from the movie set or the typewriter, committed offenses or held beliefs we as a society find repugnant. Yet, many times we have seen allegations that must challenge how we view art.

Dederer does touch on how to interpret or reinterpret art after the revelation of naughtiness by the creator(s) of that art, particularly in the irony of the Harry Potter franchise, which provided a fictional home for many kids who felt like outsiders, particularly those from the LGBTQ+ community, only to find that its author, J.K. Rowling, did not accept them for who they were. Looking back on the story and characters, what initially seemed like plot holes or missed opportunities for character growth do seem now like warnings about the clash between the main thrust of the series and the author’s personal beliefs. However, it felt as though more time was spent considering her own reaction to reading Lolita as an adolescent and as an adult to these instances of necessary reinterpretation.

Monsters, published in April 2023, was obviously already published before the launch of Quiet On Set: The Dark Side of Kids TV, which hit Netflix earlier this spring. Quiet On Set alleges mistreatment of child actors on popular kids shows in the 90s and 2000s, particularly those that aired on Nickelodeon and helmed by legendary showrunner Dan Schneider. (That there may have been issues with the filming or production of Quiet On Set is a separate issue.) Monsters may have even been written and on its way to the printing press before the August 2022 publication of Jenette McCurdy’s explosive memoir, I’m Glad My Mom Died, which included a number of allegations about a showrunner who was never named but very much sounds like Schneider. Considering many of the allegations include sexual harassment and forcing the child actors into mock-sexual situations, it seems difficult to separate the media created under those conditions from its creator. Likewise, Joss Whedon, once the darling of feminist media, has gradually and repeatedly proven himself to be a voyeuristic misogynist; Buffy, the Vampire Slayer may still have redeemable qualities, but the entire premise of Dollhouse, which once drew only the occasional raised eyebrow, is now difficult to stomach. Farther back in Hollywood history, Alfred Hitchcock may never have been canceled, but his treatment of some of his stars, especially his female ones, makes it hard to watch some of his films carefree.

These are only a few examples came to mind when reading Monsters. Then again, maybe that’s less a flaw of Monsters and more part of Dederer’s argument. No single author can cover every problematic person, nor re-examine every media potentially made. Rather, it’s an exploration of the kinds of conversations we are, or should be, having as perceptions shift and knowledge comes to light.