It’s true that cancer’s a bit of a shortcut to tragedy, as swift and unrelenting as it often is. If AJ Dungo’s In Waves were a graphic novel, I’d probably assume this was yet another The Fault In Our Stars wannabe. But this is a graphic memoir, not a graphic novel, and I would have missed out on a lovely meditation on grief. And surfing. There’s also a lot of surfing.

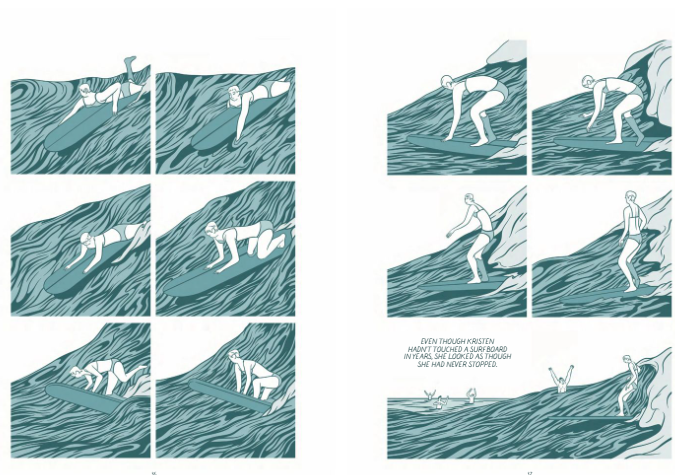

Kristen is the light of AJ’s, and many other people’s, life, and he spends his early high school years dazzled at her from afar. At long last, they get together, but the bottom falls out of her world, and his, when she feels a bump on her leg that shouldn’t be there. It’s cancer, and it needs aggressive treatment—including amputating that leg—to stop it. The treatment works, but not forever, and thirteen years after AJ first caught sight of Kristen at that high school party, Kristen dies. In the middle are once-in-a-lifetime trips and parties and living in the moment, and promises to remember all of the good times long after the person who helped make them is gone.

(This is not a spoiler. Dungo is very upfront about the outcome of this story. If you’re reading In Waves and wondering if Kristen lives or dies, you haven’t read very closely.)

Spliced between the jumbled timeline of Dungo’s personal story is the history of surfing as we know it, from the early Hawaiians to colonization to the first world-famous surfer, Duke Kahanamoku, and finally to Tom Blake, who created the first hollow, finned surfboard—a grandparent to the boards used today. The obvious connective thread between the two narratives is that Kristen loved surfing and Dungo learned and grew to love surfing through her. It isn’t until the end that another tether between the narratives becomes clearer.

Having a solid thematic knot to tie both narratives together was necessary and welcome, though it did come so late in the book that I’m not sure how effective it was. The surfing element seemed to be moving at a speed and focus uninhibited, and uninformed, by what was happening in the contemporary story of love and loss. Part of that sense might have been due to the unrelentingly linear nature of the surfing history, while the contemporary story bounces back and forth through those thirteen years Dungo knew Kristen. I’m not sure that mismatch in narrative is a feature, but I don’t know that it’s a bug, either.

Because although cancer stories are frequently shortcuts to pulling on the ol’ heartstrings, Dungo’s is seeped in just enough grief to make those sections sad without veering into cheesy. This was one I was glad I had bought, not borrowed, when a stray tear or two appeared out of nowhere and plopped onto the page. The story of surfing, meanwhile, is almost an antidote in its retelling of a history of colonization and popularity. It’s straightforward, even if it’s not an altogether happy story itself, and each section felt like a breath of air after being tumbled around by another wave of sorrow. And for two concepts I wouldn’t have thought had anything in common, Dungo does connect them well.

Dungo’s tragedy may be the sort fiction writers look to as low-hanging fruit, but he writes about it from a place of tenderness that is so evidently still not quite scarred over. Cathartic as writing this book may have been for him, it will also linger with me for a long time yet.