If you were to make a list of worst places to build an elementary school surrounded by a neighborhood geared toward young families, you might include Chernobyl, an alligator-infested swamp, maybe an old minefield.

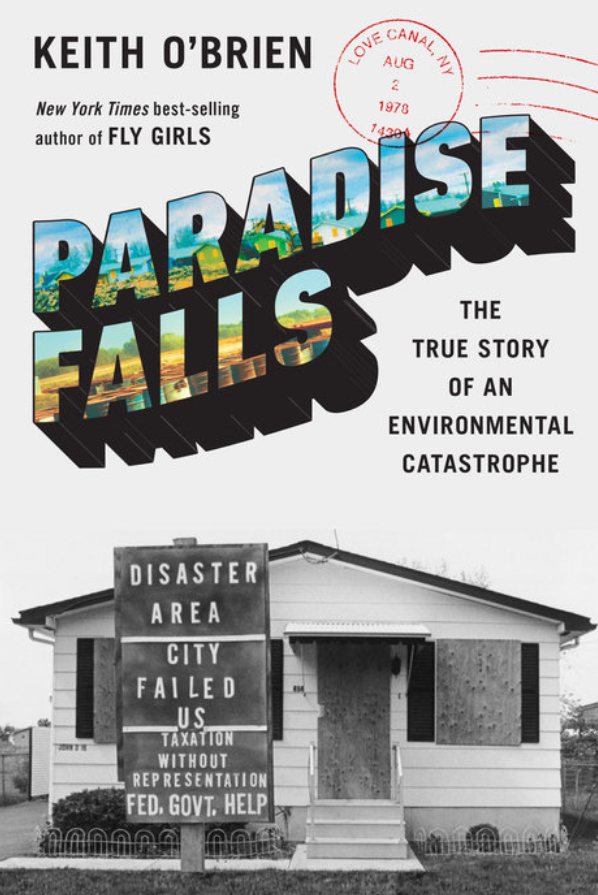

For the residents depicted in Keith O’Brian’s newest book, Paradise Falls, the extremely terrible and wholly unsafe place is an old chemical dumping ground, which for some reason causes all sorts of problems that lots of rich and powerful people refuse to believe are actually happening. And although this nonfiction story happens in the late 1970s, there are more than a few themes still eerily relevant for our world today.

The Niagara Falls neighborhood around Love Canal seemed like a quaint and quintessential American town, with young families letting their kids play with neighbors along safe streets and the rivers and ditches that peppered the areas between blocks. Sure it wasn’t perfect—the air smelled bad, even chemical-y sometimes, and occasionally kids would come home with injuries a bit stranger than the customary scrape or bruise—but for the families living in that upstate New York community, it was as close as they could hope for.

That is, except for how the smells kept getting stronger, and even seemed to migrate indoors. And how just about everyone had or knew a kid who had seemingly spontaneously come down with asthma or leukemia or something, and how there seemed to be a lot of miscarriages going around. As word began spreading, and as strange substances started bubbling out of the ground around the canal, those oddities took on a sinister new light. Because under the neatly trimmed lawns and white-picket fences of the Love Canal neighborhood lurked barrels and barrels of chemical waste from the city’s largest employer, Hooker Chemical, quietly buried in the 1940s and 50s before selling the land to the city and school district for just a dollar—as long as no one asked too many questions. As their children got sicker, parents in the neighborhood began to take notice. The resulting fight for environmental responsibility would reverberate all the way up the White House and splash across the country on newspaper headlines.

O’Brian rightly picks a few key figures to guide us readers through a fast-paced and multi-layered tale that is at times so explosive (pun mildly intended) that it’s easy to forget it’s nonfiction. Lois Gibbs, who eventually becomes known as the “Mother of the Superfund” for her grassroots efforts to bring attention and change to the situation, is an obvious main character to follow, especially considering the press she got at the time. Less obvious, though, are Luella Kenney, a scientist and mother of a child who develops a mysterious and serious kidney disorder, and Beverley Paigen, a scientist who didn’t live in Niagara Falls but who partnered with Lois and researchers from the state and the EPA to try to decipher the actual rate of illness among residents from the anecdotes and rumors that flew around. O’Brian also highlights Elene Thornton, a Black renter whose son died of leukemia before the age of two. There are plenty of villains to contend with, too, including sexist bureaucrats, politicians on the campaign trail, and Armand Hammer, the elderly executive leading the parent company of Hooker Chemical.

The story is told in a strong narrative style, making this a page-turner. But it’s also well sourced, too, with sixty pages of notes. Despite the events happening nearly fifty years ago, some of the players were still alive for O’Brian to interview and get documents and pictures from, giving personal insight into a story already primed for emotion and outrage. As a result, the narrative feels fresh as it goes through Gibbs’ transformation from high-school grad mother to community organizer; Kenney’s helplessness and sorrow as she fights for her son’s care even as he gets sicker and sicker; and Paigen’s outrage as her work is stymied by her bosses for what she feels strongly are political and sexist motivations. Thornton, unfortunately, gets comparatively little of the pie, which is particularly unfortunate for the perspective she brings to the underprivileged micro-community of her housing development. She was almost ignored at the time, too, especially when the press had the more conventional heroine of Gibbs to write about. As O’Brian notes, Thornton passed away in 1987, making her a poor interview subject, but it’s still an unfortunate, if unavoidable, limit on the story.

The prelude to Love Canal and its aftermath both feel alarmingly prescient in our world of violent weather events, rampant pollution, and politics that frequently feel dismissive about addressing the climate. If the key to a good story is something that feels both firmly rooted in the time and place where it’s set while feeling universal and pressing, then Paradise Falls opens the lock with ease. There’s nothing feel-good about it, but there is something inspiring to read about the ultimately successful efforts of another era—even if the people making that effort had to pay a hefty price along the way.