The thing about someone having the worst day of their life is that at that very moment someone else is having the best day of their life. There are enough people and enough days and enough experiences to account for the polarity of best and worse and everything in between.

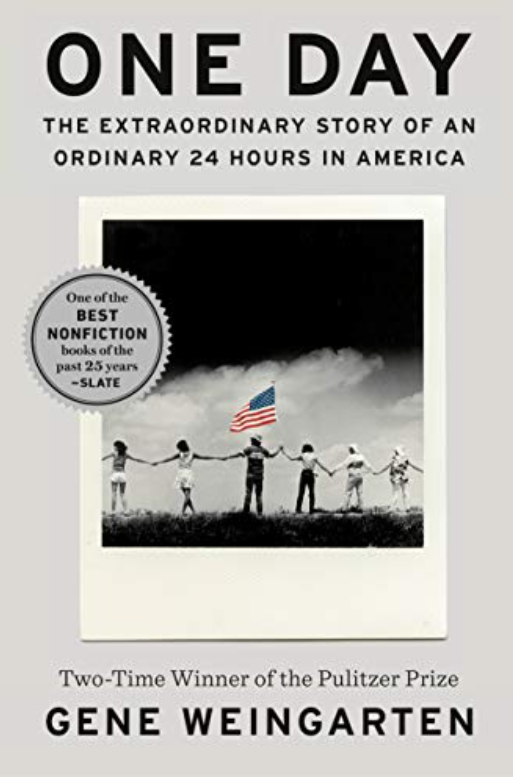

Those stories existing is one thing. Finding and telling them compellingly, though, is another. Which is why I was endlessly fascinated by every page in Gene Weingarten’s One Day: The Extraordinary Story of an Ordinary 24 Hours in America. The two-time Pulitzer Prize winner has turned his longform reporting chops to making a story out of a random and hardly newsworthy day.

The premise behind One Day is simple: finding out the highlights of one full day from the past. The day pulled from the hat by strangers is December 28, 1986, which worries Weingarten at the outset for a couple of reasons: first, it’s the week between Christmas and New Year’s, when apparently people are too stuffed with holiday goodies to do anything interesting. On top of that, December 28 was a Sunday that year, and everyone knows nothing interesting happens on a Sunday. Weingarten tells all this in the introduction, presumably to lower reader expectations.

This is unnecessary, because from 12:01 a.m. right up to 11:55 p.m., One Day is filled with story after story about people’s best days, their worst days, their epiphanies, their turning points, and the breaks in mundanity that can color any day—but in this case, all happen during the course of a single day. Events include two deadly fires in different parts of the country, a missing weathervane, a video game triumph, a historic heart transplant, murder, a helicopter crash, an impulsive engagement, and a surprisingly perfect performance by the Grateful Dead. The events themselves are fascinating, but what happened next to each of the people involved only expands those instances to compelling stories.

For the most part, Weingarten’s storytelling is empathetic and even-handed, exploring the various events sensitively but with the distance of a journalist. He is as matter-of-fact about the death of a baby as he is about an early and pivotal use of the instant replay, but he’s also as impassioned about each of those things. You get the sense that Weingarten is excited about people and the odd little things they do, the big things that happen, the choices they make before and during and after. He doesn’t miss a chance for a well-placed bit of irony when the situation calls for it, but knows when to pull his tongue out of his cheek, too.

This book is not groundbreaking journalism. It didn’t win Weingarten another Pulitzer, nor, I suspect, did he ever expect it to. It won’t change policy or right injustices. It might, however, make its readers more empathetic. I left One Day wondering about the little moments in my life, how a chance encounter here or a random tragedy there fit into the tapestry of crazy random happenstances—and made me think more empathetically about those around me and whatever kind of day they were having. There’s a lot that life offers, and One Day offers a glimpse of it.