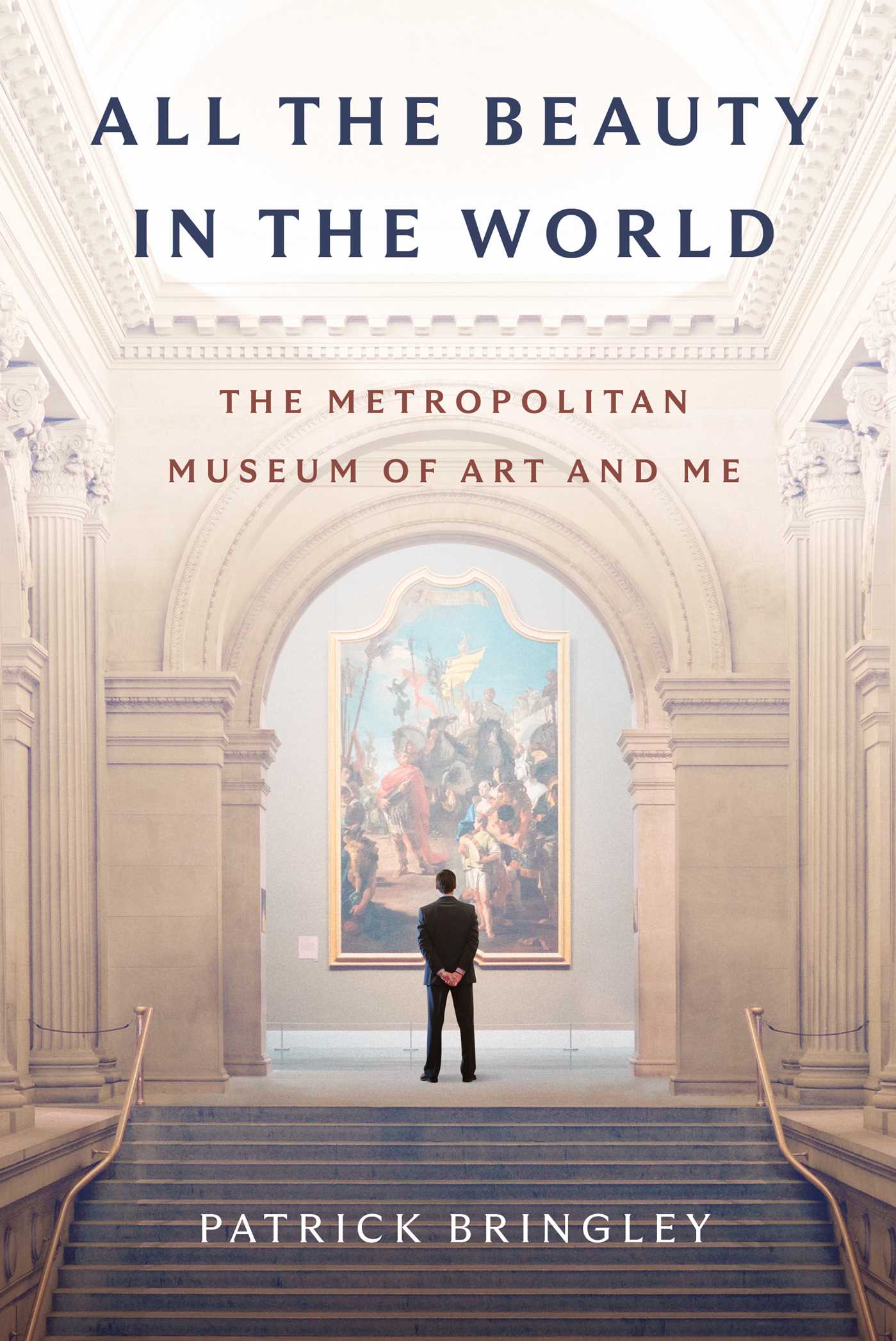

It would have been easy for Patrick Bringley to have written a sappy story about art healing him after his brother’s death. It could have also been easy for him to give us a travelogue of his ten years working as a guard at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Instead, All the Beauty in the Word: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Me threads the needle to make something heartfelt but not cheesy that dances in the space between the mundane and the profound.

In 2008, Bringley’s brother, Tom, died following a long and difficult battle with cancer. With Tom’s death came the realization that little in Bringley’s life fit him in this new state of being, so he quit his job at the New Yorker to take up the “cheap polyester blue suit” uniform of a security guard at the Met. Bringley had loved going to the museum as a child, which at that time required that his mom and siblings travel from Chicago. As a guard, he found his experience as a kid hardly scratched the surface of the museum, or of the works, and people, within.

There are the works, of course, by well-known masters and unheard-of craftspeople alike. But a casual visit, Bringley observes, is for viewing the works as aesthetic objects; staring at a piece for a long time—like you might if you were a regular, an art student, or, say, a guard—results in a different relationship with the displays. Bringley describes being taught by the pieces, being in conversation with the pieces. At times, this approach veers on the pretentious, but his earnestness reins it in.

Enthusiasm also keeps his observations about people, both patrons and colleagues, from sounding judgmental. He delights in the diversity of the Met’s workforce, noting that it’s normal among his coworkers for one person twice the age of the other, and both born on different continents, being close friends. He compares that to his experience in white-collar jobs, where people often come from similar backgrounds and demographics. How true that is may be debatable, but the interest he takes in his fellow guards and their respective stories feels genuine.

Grief is unavoidable in this present-tense memoir; however, it functions more as a catalyst than a throughline. Tom’s death laid bare the parts of Bringley’s life that no longer suited him. Over the ten years he works as a guard, he finds the routine and the stillness, the patience, the job requires to be grounding amid an existence that has lately been anything but. This is a story about a person reflecting on what they need rather than what’s expected of them, and it’s a point of view that has lingered with me since finishing All the Beauty in the World. The main narrative may be focused on fine art, but Bringley’s observations go far beyond that, to the point that I found myself contemplating the beauty of weeds sprouting through a crack in the sidewalk.

This is a book of stillness, and a book of contemplation. It’s a book about appreciation, and of change. Life, broadly, is all of those things, and All the Beauty in the World shows the value in recognizing that a little more.