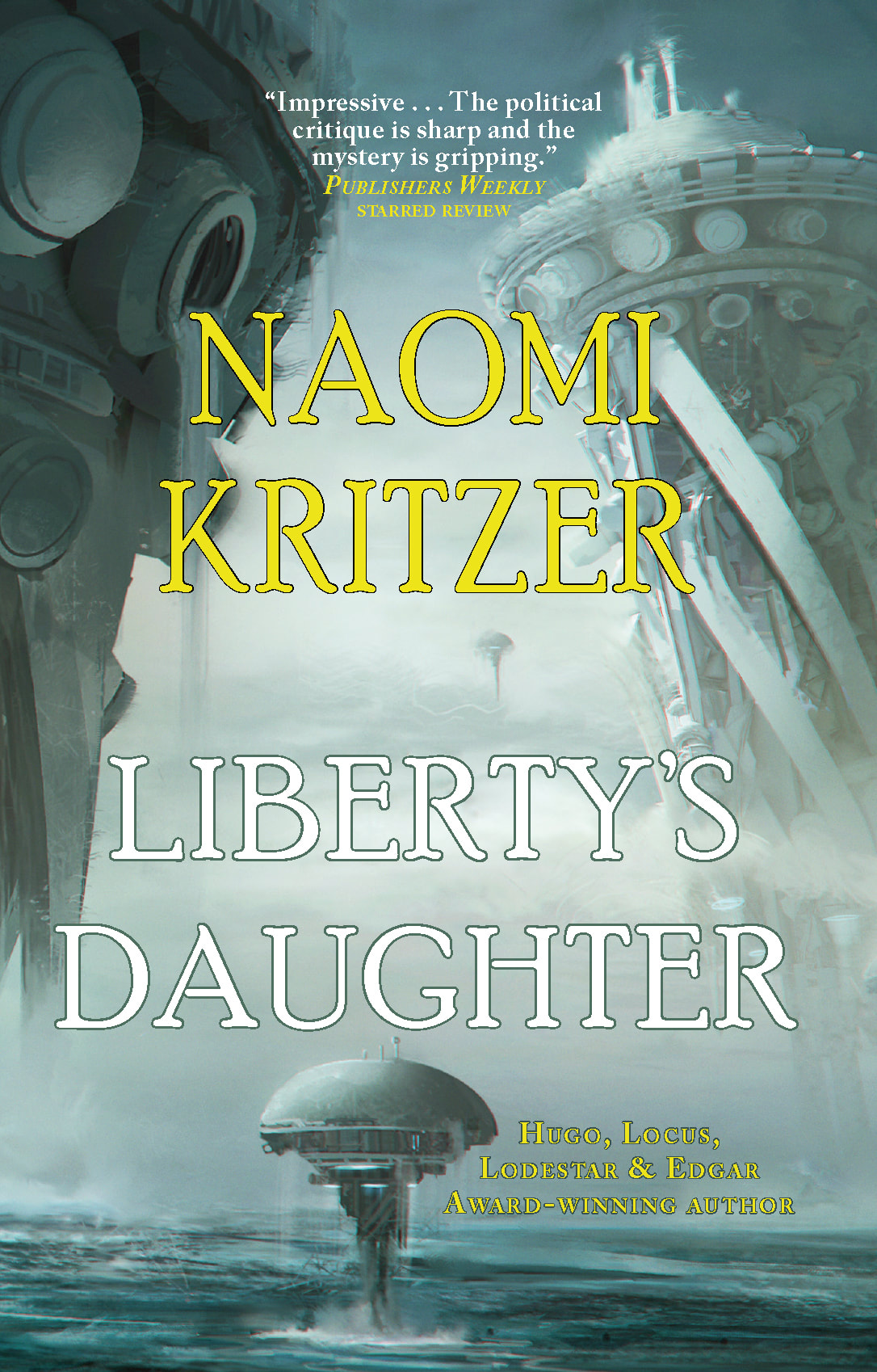

Naomi Kritzer’s breakout short story “Cat Pictures, Please” made me an instant fan, though that’s not exactly original of me—that story was a finalist for the 2015 Nebula award, and took home the trophy for best short story in the 2016 Locus and Hugo awards. I loved the blend of playfulness and emotional resonance, which I’ve found in other stories of hers since. That trademark combo holds true in her latest novel, Liberty’s Daughter.

The near-future seastead that 16-year-old Beck calls home may be free of laws and other government interference, but it’s got plenty of rules and customs that can be tricky to observe. Luckily, she knows them like the back of her hand, which comes in handy when she starts doing odd jobs for pocket money. In the manmade archipelago of strapped-together platforms and ships, shipments of new supplies are scarce, and it turns out people will pay cash to whoever can find them a pair of high heels or other hard-to-come-by items. When Beck’s fledgling find-it service sends her to seek out a person, she unwittingly stumbles into a black-market trade of indentured workers.

Her powerful father helps smooth the feathers she ruffled by asking the wrong (or right) questions to the wrong (or right) people, but that’s only the beginning of Beck’s entanglement with the more complicated parts of the seastead. The more she learns, the less, she realizes, she knows about the seastead, and her father. But she’ll need every scrap of that knowledge to stay afloat as she gets involved with a reality television show, and as a bizarre pandemic sweeps across the seastead.

Liberty’s Daughter, like Kritzer’s earlier novels Catfishing on CatNet and Chaos on CatNet, developed out of previously published short stories. Maybe that’s why Liberty’s Daughter feels so episodic, though there are plenty of narrative threads binding those episodes together. Each, too, peels away another layer of the seastead and the circumstances that brought Beck there. Sixteen is a difficult enough time in life without having to track down labor slaves and pass along secret messages among the proletariat—or find out whole portions of your life have been a lie. Beck’s resourcefulness, though, saves the day, and the seastead, more than once. And while a heroic teenage girl is a staple of YA speculative literature, Kritzer manages to make those heroics feel plausible with Beck in the situation she’s in.

Beck is an easy character to love: she’s open and observant, and her explanations of this or that in the seastead manage to be informative without just dumping info on the reader. She’s also old enough to just begin to understand the way the world works while being young enough to believe it can change. That crucial quality removes us just a step away from some of the darker elements of Liberty’s Daughter, letting us understand the dark side of the libertarian wet dream she calls home without this book straying into the horror or dystopia genres. For all its many faults, the seastead isn’t quite a dystopia, though some elements do drive home the need for, say, labor laws. More than anything, Liberty’s Daughter is a story about finding your way in the world—an easy message to relate to, even for those of us living on dry land.