Recently, I faced reality and brought my hummingbird feeder in for the year. It was long overdue—I haven’t seen a hummingbird in a few weeks and the nectar itself was over a week old—but seeing the bare hook outside my window was a sign of the cooling weather and waning year as much as any color-changing leaves or Christmas decorations going up in stores. At the regular bird feeder, it’s pretty much down to the sparrows, with doves and the occasional spooky season-appropriate crow pecking at the ground for what the sparrows have spilled. With these kinds of bird-related thoughts on the brain, Amy Tan’s The Backyard Bird Chronicles was an utterly timely read.

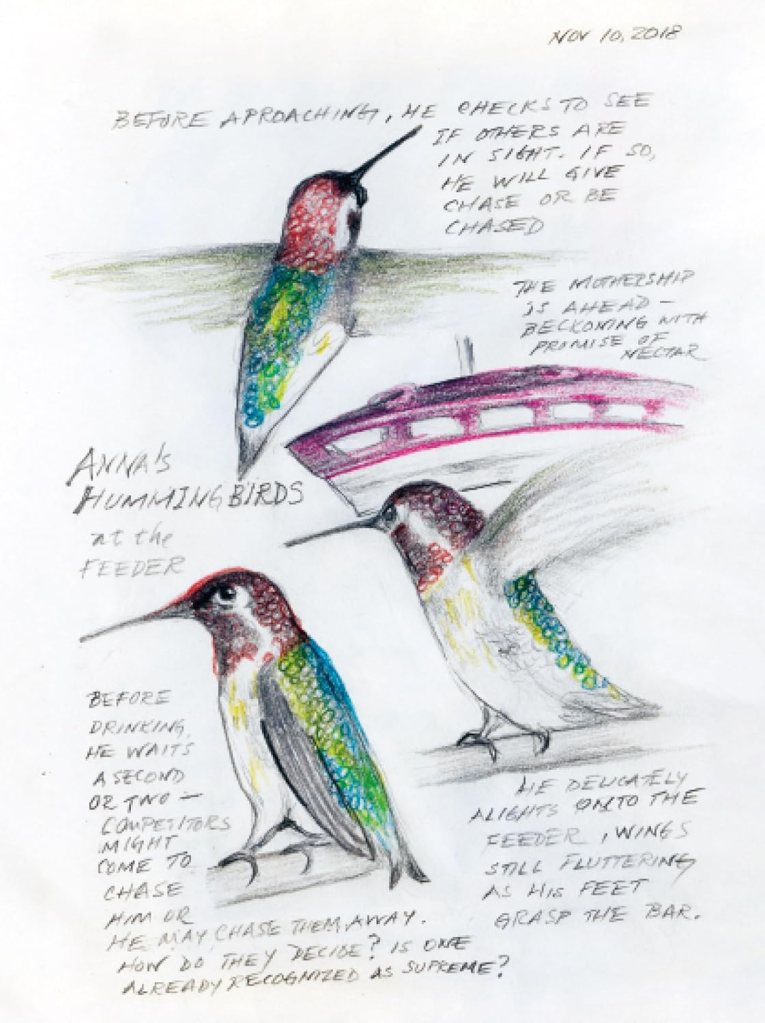

Beginning in 2017, Tan began recording the various avian (and mammalian) visitors to the yard of her Sausalito home in journal entries and pencil drawings. From hummingbirds to goldfinches to siskins to birds of prey, Tan took notice of the animals coming and going. Who ate what, and how to keep the squirrels and rats from hogging the food set out for the birds. How fledglings learned to fly and eat on their own. Who comes and goes and at what time of year. In her sketches, she often jots down little observations or interactions, a handwritten record of the day’s birding. It’s lovely and intimate to read such inner thoughts of another person. It’s intimate, too, to see her drawings improve over the years and the birds within them grow increasingly lifelike.

The Backyard Bird Chronicles covers nearly five years of Tan’s journaling and sketches. Right in the middle of that time is, of course, the COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdowns associated with the spring and summer of 2020, and in some ways stretching into 2021 and the advent of the vaccine. A lot of us were taking more notice of our surroundings during those weeks and months—there wasn’t much else to do and certainly nowhere to go—but Tan’s account is almost business as usual. Mealworms still needed sorting and eggs were still hatching, irrespective of petty human affairs. There’s something comforting about that lack of novelty, and I expect it’s also a quality that will keep Chronicles relevant as the pandemic fades into history.

Tan writes that her aim with taking up birding, in making her yard as tantalizing for birds and bees as could be, was in part driven by a need for some rest from the shouting of the world and politics and social issues and misinformation. Though there is a preface, there is no start to the journal, no, “Hello, world,” or statement about what she hopes to fill in the blank pages before her. Likewise, there is little reflection at the end—more a promise of more journaling and drawing to come. There’s no plot, per se, but there are little narratives that unfold: finding a victim of a bird pandemic; having to remove and disinfect the feeders after seeing signs of another avian sickness; the saga of trying to keep squirrels and rats and hornets away from the birds’ food. In all the best ways, Chronicles feels like a glimpse through someone else’s window.