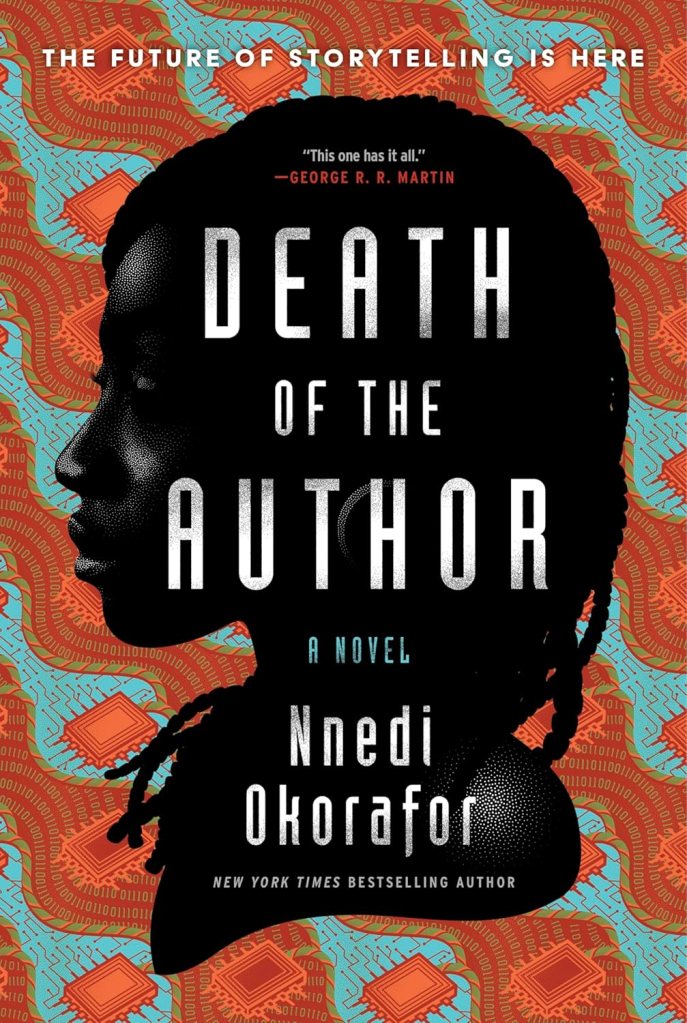

There’s been no shortage of discussion about various creatives or personalities “canceled” (or worse) for one thing or another, and what to do with the content that has their name, and their brand, all over it. Nnedi Okorafor tackles this disturbingly timely topic in her latest novel, Death of the Author.

Zelu has always been different than the rest of her Nigerian-American family—because she’s paraplegic, or in spite of it? Not content to follow the expectations of either starting a family or embarking on a respectable career, she keeps having one-night stands, adjuncting for whiney graduate students, and hoping a publisher will appreciate her pretentious literary novel. The night of her sister’s wedding, Zelu gets fired from her adjunct job for yelling at a student, her novel gets rejected, and she slides quickly to rock bottom. There, she scraps any pretense of literature and writes about robots.

At the encouragement of a friend, she eventually sends the finished manuscript to her agent. Within days, the robots have gotten her a book deal and been optioned for a movie, and Zelu’s life is forever changed—mostly in ways she can’t possibly imagine at the beginning. In good ways, certainly, with a hefty advance and unexpected opportunities that expand her world in both figurative and literal ways. But there are challenges, too, especially with her instant notoriety that only increases as fans clamor for more robots. As she grapples with both the good and bad, family and personal tragedy both take their shot at Zelu—as do love and a renewed sense of self. All of it goes into forming the author, and none of it is wholly untangled from what ends up on the bookshelf.

For anyone not familiar with the phrase, “death of the author” refers to an argument within literary criticism that art should be consumed and considered separately from the beliefs or background of its creator, and validates readers’ interpretation without the constraint of the creator’s intent. This framework does allow for many interpretations, and lets a piece of art grow far beyond the constraints of reality or imagination that its creator might have had. But while the theory doesn’t call for completely ignoring creator, it does greatly diminish the creator’s role once the art is released to an audience. In this age of scandals and allegations, its usage is often used to consider whether one can continue enjoying art made by someone who has broken the social construct in some way, from having a bad take to being accused of serious crimes.

Interspersed with Zelu’s story are chapters from her robot book, the themes of which both parallel and contrast with what we learn of Zelu’s life. Her main character’s legs are damaged and have to be replaced. In a future Nigeria that sees the death of the last human, her robot characters feel displaced—not fully from one place or another, not belonging to a single group of people, always feeling and being told that they are different. Of course, no author can avoid putting drops of themselves in their work in some way, and this is true of Zelu—but how much does that matter? For many of her fans, it’s seemingly impossible to keep from speculating where Zelu stops and her characters begin. She is not the personable hero her fans want her to be, but she is also not any of the things they call her when she criticizes the film adaptation of her book or simply drags her feet, metaphorically speaking, in writing that darn sequel. At the same time, both the film adaptation of her book and the fan fiction it elicits shows Zelu how misunderstood she really is. When she thinks about writing a sequel, part of her reluctance comes from not knowing to what extent her fans will expect the same altered interpretation from her.

This is a fascinating week for Death to be released, especially for the publishing and SFFH communities in the wake of the explosive Vulture article (paywall-less version here) that expounded horrifically on last summer’s allegations about fan favorite and outspoken “feminist ally” Neil Gaiman. In a way, it seems unfair for a book about the tangled mess that is art and artist, and the assumptions we tend to make about where one ends and the other begins, to come out under these circumstances. On the other hand, what’s better advertising than a book about the very thing so many of us are grappling with yet again?

The question of “death of the author” and how much an audience really can separate creator from creation—or how much we should creatively and financially support those who think or behave in ways we disagree with—is not one that can be answered in one book (or two), or with one scandal. Zelu, though an intriguingly difficult person, and character, to love, is still a basically normal person, albeit an impulsive one with a wickedly sharp tongue. She’s a good balance for Okorafor, I think; if she were nicer or a lot worse, Death wouldn’t challenge the question at all. Zelu isn’t a regular person, but she’s a realistic one (robot legs aside). More importantly, Death has a lot to say about art, its creation, and those who make it for us that is more relevant than ever.