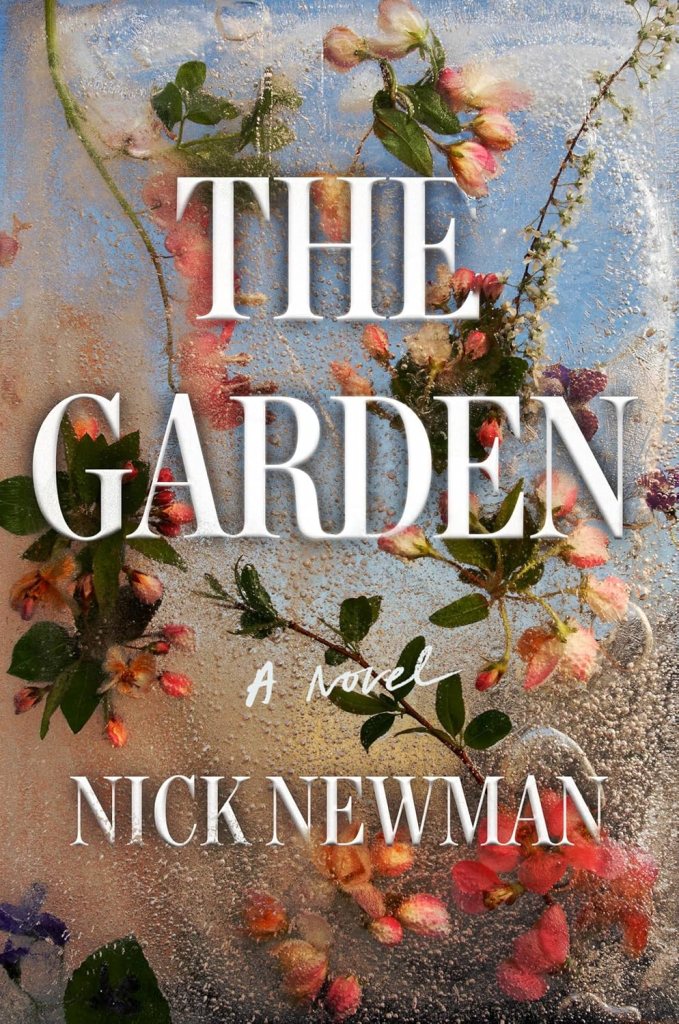

Post-apocalyptic stories have enjoyed a long popularity, likely in part due to a world that refuses to return to any semblance of “precedented times.” I know I’ve thought about the possibility that everything goes to hell. How long could I last on just what I could grow and preserve on my own? (Answer: not long.) But these stories often center the first few years after an event. The Garden, the adult debut from Nick Newman, instead explores what happens when self-sustenance and isolation last for a lifetime.

Evelyn and Lily live small lives: Evelyn tends to the vegetables and bees, while Lily does the cooking, and the two elderly sisters ramble around the part of their childhood home they’ve confined themselves to since they were young. But amid Lily’s continued practicing of the dance routine she’s been working on for decades and Evelyn recites the one book they have for the nth time, Evelyn also starts noticing little oddities: a beehive out of place, a shadow she can’t explain, food missing from the kitchen.

The culprit is a teenage boy who has slipped through a hole in the wall that has protected the garden and the house within since the world went to hell. Evelyn can’t bear the thought of him starving and being hurt, while Lily wants to do away with him immediately. Both fear that his presence is only the first of the dangers that might finally come to their door. As the newness of the boy’s presence wears off, Evelyn’s fear only grows, while Lily seems to have lost hers—even of the things the sisters have been avoiding from the start. Suddenly, it’s not just their safety at risk, it’s their relationship, and their entire little world.

We get few details about the world or what happened to it, other than things are very, very bad. In flashbacks to the beginning of the end, there are glimpses of supply and provision shortages; the girls’ mother and father argue about whether to stay or go from the estate, and whether to wall themselves in or leave in search of safer ground; a small group of looters arrive when it’s just the girls and their mother in the house, demanding everything they have and more—or else. Evelyn is just a few years older than Lily, but it’s enough to give her a fuller picture of what their mother was trying to shield them from while Lily’s understanding is limited to vague threats of monsters beyond the garden’s walls. And that discrepancy in how much each understands of the world outside affects how she perceives the new

One of the most interesting aspects of The Garden is how overgrown the childhood relationship between the sisters has become over the years. They’re both now old enough to know they should be watching for early signs of dementia in the other, but their dynamic has remained unchanged over their lifetimes, as if the lack of outside influences prevented them from growing up, too. Lilly still defers to Evelyn, even while complaining about how Evelyn is bossy and always in charge. They both defer to their mother, though she doesn’t talk back much from her grave, and it’s clear that even the garden has outgrown her guidance. Decades of love, history, resentment, and childlike obedience that should have expired a lifetime ago make for a potent stew for these sisters to sup.

In many ways, The Garden is as much about the testing, and mending, of that sisterly relationship as anything else. The apocalypse is merely a reason for their cloistering, and the reckoning they face with each other—and how and why they’ve spent their lives within these walls.