Heads up: suicide is a strong and persistent theme in this book, and consequently in this review. Take care accordingly.

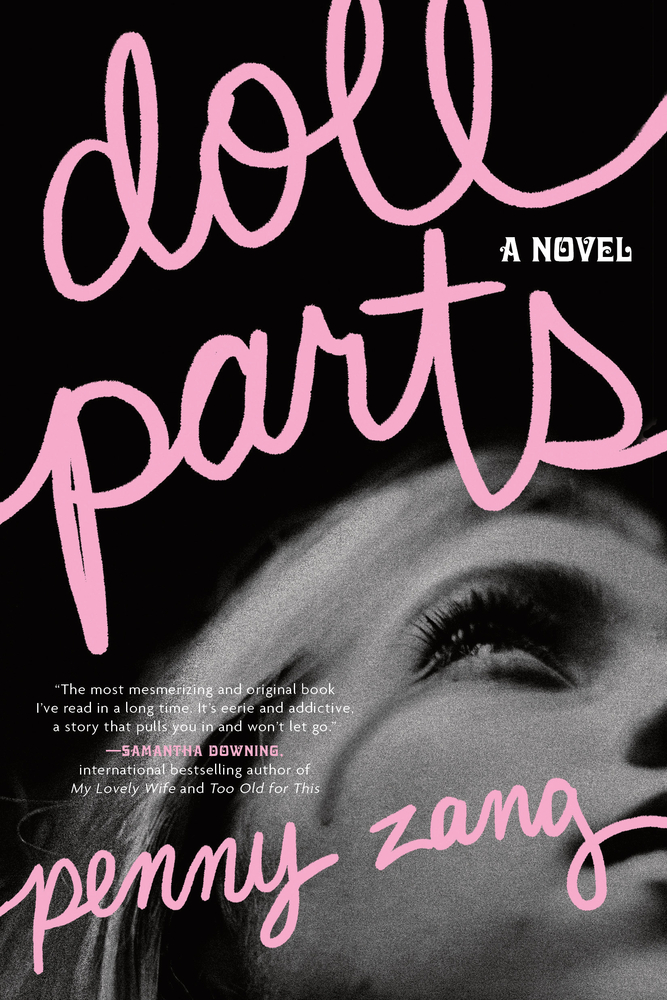

There’s something unique about childhood friends, the people who see you through adolescence and into adulthood and know your secrets and struggles from that time with an intimacy that platonic relationships down the road usually can’t accomplish. That’s not to say childhood friendships always, or even usually, last with the same power as lives diverge, but the love and connection often linger. That’s the case in Doll Parts, the debut novel from Penny Zang.

Doll Parts is a novel made up of two genres blended together. First up is Sadie, who, in a domestic thriller sort of plot, finds herself, twenty years after college, raising a baby with her ex-best friend’s widow. Despite not having seen or heard from Nikki in almost two decades, Sadie came to her funeral and ended up sharing more than grief with Harrison. The pregnancy might have been accidental, but her baby turns out to be a great distraction from how much Nikki’s adult daughter, Caroline—and what seems like all the women in this upscale neighborhood—hate her guts for being the interloper. On top of that, she’s started seeing Nikki’s ghost around the house. Postpartum psychosis? Seems less like that when she starts finding some pretty big clues from Nikki for Sadie to pick up where she left off. Which, of course, she does. Nikki’s death was an accident, or suicide, but it doesn’t take long for Sadie to figure out there’s more to the story.

Meanwhile, twenty years in the past, Nikki’s story is one of sharp dark academia. At the private all-girls university where Nikki landed a scholarship, professors might be life-changing mentors or wolves in sheep’s clothing and someone or something’s been killing the girls in this so-called “Sylvia Club,” named for the entire campus’s obsession with Plath and other beautiful dead women. Alarmingly for Nikki, most of those girls are just like her: from underprivileged backgrounds, on scholarship, drowning under the weight of the requirements for keeping that crucial funding. The last few victims of this supposed curse or club is Dr. Weedler, the classic deeply invested professor who hides rampant misogynism behind a thin veneer of allyship. His, uh, hands-on approach to mentoring is known to many of the girls, and to Dr. Gallina, a female professor who seeks out and mentors struggling girls with promise, but who might herself be a little too invested in their struggles. To make matters worse, Nikki, already emotionally haunted by her mother’s recent death, sees the ghosts of the dead girls everywhere she goes, and they demand she find answers for them.

Two types of plots, two very different voices, and putting them in concert is a little rocky, until it isn’t. When the clues start coming together, it feels like a satisfying and cohesive two-lens story, though until then Sadie and her post-birth isolation can be stifling. It’s much easier to get into the familiar stress and excitement of campus life through Nikki, and the biting quality of her voice (and her well-earned grievance) help propel the story onward. There are clues early on that not all is well, and that’s before anyone starts talking about dead students or ghosts. But in the same way that generations of people (mostly women) have had to bend under the will of powerful people (mostly men), that tension, too, is familiar. Sadie and Nikki were well matched as teenagers, but both as a younger voice and at the margins of Sadie’s story, it’s clear that Nikki is the one with all the momentum for the pair.

That said, it was gratifying seeing Sadie awake from her stupor of grief and radical life changes. She may be the one seeing ghosts, but she’s also living like one when we meet her, hardly taking up space in her ex-bestie’s house with her ex-bestie’s ex surrounded by her ex-bestie’s things. It’s only through the needling of Nikki’s ghost, and Sadie tumbling through memory and the mystery Nikki left behind, that she begins to come back to life.

But friends can do that, sometimes. Even when two people have grown apart at some point, life may bring them colliding back together, and memories made during a formative time have a habit of sticking around. The mysteries and deaths and drama in Doll Parts are merely details to that time-worn tale of lasting, if not always active, friendship.