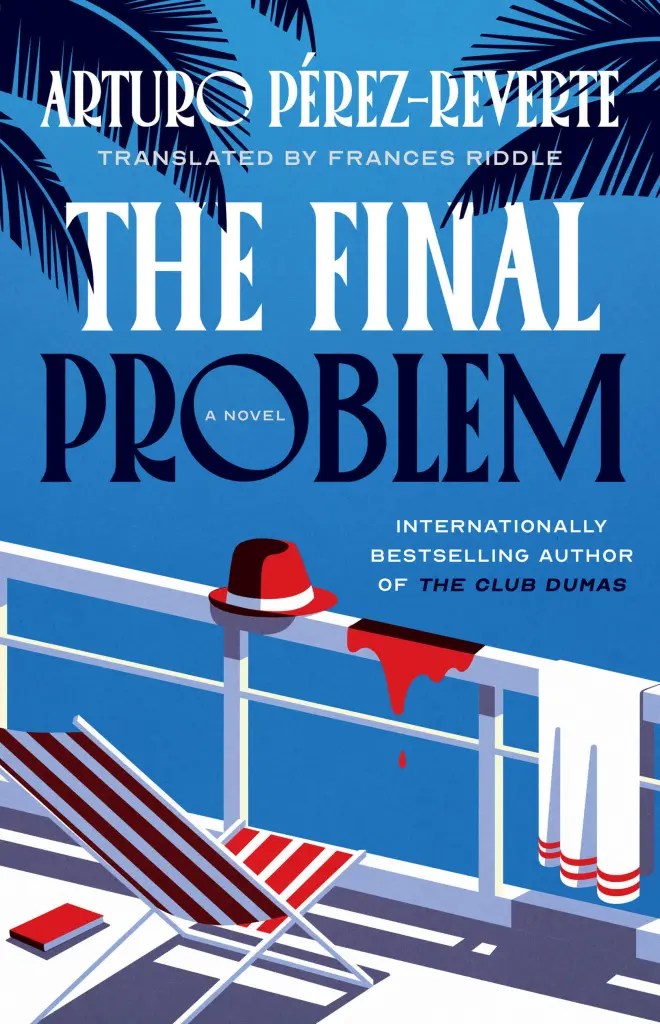

In glamorous 1960 Europe, a chance encounter between those on both sides of the second world war, and Hollywood’s golden-age camera, makes for a deadly combination. That’s the setup in The Final Problem, the latest from Spanish writer Arturo Perez-Reverte, now translated into English by Frances Riddle.

Ormond Basil, a one-time movie star now flirting with obscurity, takes a holiday to sail the Mediterranean with his producer friend and new arm candy, but a storm forces the three and the other passengers to take shelter at a quaint inn on a remote Greek island. If everyone weren’t already on edge, the apparent suicide of one of the guests doesn’t help matters, especially since not everyone believes it was suicide. Basil isn’t Sherlock Holmes, but he does play one on TV—or, rather, the movies, fifteen of them over his all-but-faded career. That’s good enough for the other residents at the inn, especially as the raging storm prevents the local police from coming to solve the case, or at least allay the guests’ fears.

As Basil questions the other guests, flanked by a Spanish writer deputized as his Watson, his own doubts about the apparent suicide grow. Doubt turns to suspicion and fear as another murder follows. With the winds still raging and no evidence of a soul on the island besides the guests and staff, the walls of the inn seem to draw closer. Is this a case of love, or lust, gone wrong? Are the deaths a ripple from World War II’s ending fifteen years past? As the killer, or killers, become bolder, it becomes more difficult to tell clue from red herring, and even Basil, the closest thing the world has to Sherlock Holmes, may not be able to crack the case.

Basil is the reluctant detective pressured into service, but it becomes clear to the reader, to some of the characters, and even to himself that he’s getting real pleasure out of the puzzle, especially the more the culprit, too, seems to be engaging in this deadly little game. The depth of his embodiment of the fictional detective becomes clear as the mystery unravels, even without multiple characters explicitly saying so. It’s fun to see him leaning into this observational deduction, and Perez-Reverte manages to make Basil feel like a unique take on the Sherlock trope amidst over a century of adaptations, homages, and reboots.

As a casual Holmes fan, I enjoyed the references to this story and that, to this aspect of Holmes’ character and the tropes he both established and redefined. Even the book’s title is a reference, to the short story that introduced us to Professor Moriarty. But as only a casual Holmes fan, I’m sure I missed a lot that a more dedicated reader would have caught and had opinions of their own to share. Being aware of but not appreciating the intricacies of these Holmes references gave the sensation of being in a conversation with a group at a party only to have part of the group delve very suddenly into the minutiae of the topic at hand: informative, not unpleasant, but also unable to do much but let the sudden detail wash over me.

But, of course, Basil isn’t only a temporary amateur detective. His long career onscreen and on stage—including but not at all limited to his time playing Sherlock—is the subject of much curiosity from the other characters, and reflection from this aging star. There are plenty of names dropped as Perez-Reverte secures Basil’s place in the entertainment orbit, though at times this talk of Hollywood and stardom lingers longer than necessary. Although The Final Problem is barely over 200 pages, it was in these passages that the mystery felt like it was dragging its feet and waiting for the next clue, or body, to appear.

Still, those moments, slightly long and frequent as they may be, did give the sense of walking behind—if not an old Hollywood set, then certainly the public life of someone who used to frequent those hallowed soundstages. That sort of reminiscence is what is perhaps really at the heart of this book. The Final Problem is a look back on old Hollywood and old regrets, a dance between a person’s previous and current selves. And, of course, there’s murder.