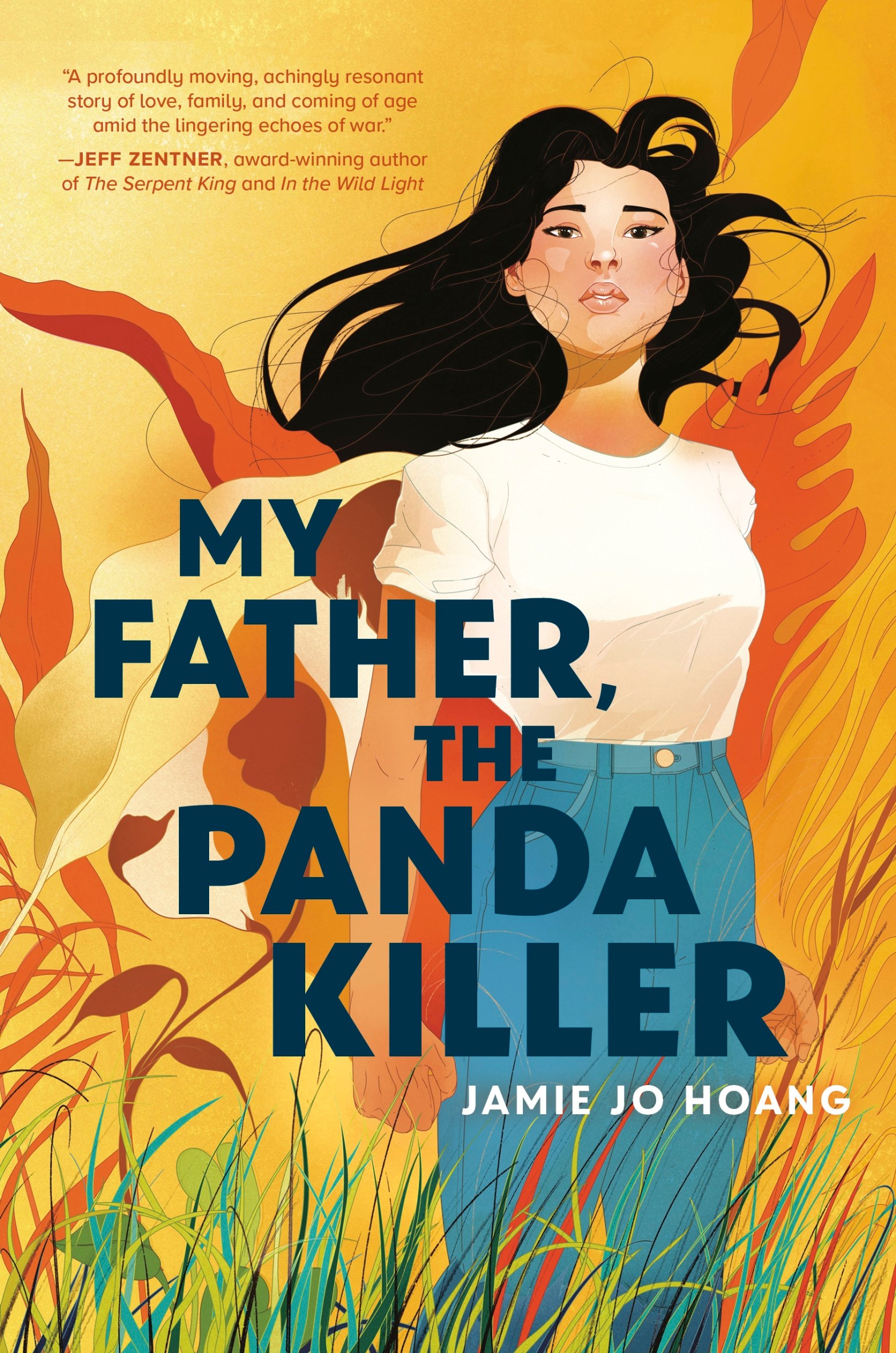

The space between high school and college is often really the gulf between adolescence and adulthood—leaving home and departing from the way things have always been done (even in small ways). It’s also a time when a person’s view of their upbringing can be brought into sharper focus than ever with the exposure to new people and ideas, or just a little distance from what was the everyday. While that’s usually a drawn-out process that often takes years to complete, if ever, it’s encapsulated in Jamie Jo Hoang’s excellent My Father, the Panda Killer.

Jane is afraid to tell her family that she got into UCLA and will soon be leaving the family’s home in San Jose. Specifically, she’s afraid to tell her Vietnamese refugee father for fear he’ll forbid her from going and make her keep working in the family’s liquor store. Even more frightening is telling her younger brother, Paul, to whom she’s been essentially a surrogate mother since their biological mom split four years before. At the same time, she know she can’t stay home. Although she loves her family, her father’s hair-trigger temper makes even minor and honest mistakes a minefield. Home, too, is still haunted by the memory of Jane’s mother, who seemed to resent motherhood and Jane’s father equally. But the more Jane learns about her father’s cloaked past, the more she wonders what circumstances really brought him to San Jose, and why the stories about who he was as a boy are so different from the person she’s known for seventeen years.

Meanwhile, Phúc (rhymes with “duke”) loves his home in the south of Vietnam, a place so connected with the earth that his flute never plays the same tune twice. Rumbles of war brings tragedy and shame in the form of his older brother running away from home to join the North Vietnamese army. Whatever hardship Phúc and his family thought they bore from that scandal is nothing compared with the suffering and destruction that gets heaped upon their heads, as well as those of their friends and neighbors as civilians are caught in the crosshairs of other people’s war. When conditions get bad enough it seems unsafe to stay any longer, Phúc and his siblings are sent away—separately, in hopes that at least one of them will make it to the safety of the U.S. Without his family, though, Phúc is forced to face the myriad dangers alone, from his own kin to Thai pirates to the unwavering elements.

My Father, the Panda Killer is an odd dual-POV story in that both stories are, technically, being told by Jane. Fortunately for both points of view, Jane is an engaging voice who feels like a genuine teenager—albeit one who’s had to take on far too much responsibility at much too young an age. Her friendship with Jackie, another kid of Vietnamese refugees, is bursting with that consuming closeness adult friendships generally can’t muster—not even the ones that start out as close-knit as teenage relationships. She’s at once judgmental and protective of those around her, and it’s that paradox that keeps more difficult events from being as shocking as they could be.

There’s corporal punishment in this book, and it goes far beyond the spanking of a misbehaving child. Hoang’s descriptions of this abuse are kept from gratuity only by the normality that Jane gives them, as well as the love for her father that persists despite the violence at home. The violence Phúc experiences during the war and as a refugee is likewise blurred, mainly by the storytelling nature of his sections. The result is that I found the story plenty heavy but never unbearable. And there are moments of levity, and of hope, and joy, for both Jane and Phúc, even as their circumstances make life a little darker for them than for others. It’s particularly Jane’s growing understanding of her family’s history that lifts the narrative as a whole. As she learns more about the past, and sees more of those despised habits within her in the present, gives even more nuance to her family situation. All of it, she learns, is crucial to breaking the cycle she’s been trapped in.

Few families are without skeletons in the closet, and seeing the power recognizing and disarming those skeletons can give makes for an inspiring story. Often, I’m hit and miss about reading a sequel to a book, even if it’s one I really liked. In the case of Panda Killer, the author’s note about a book focused on other family members has me itching to hit “preorder” as soon as it appears.