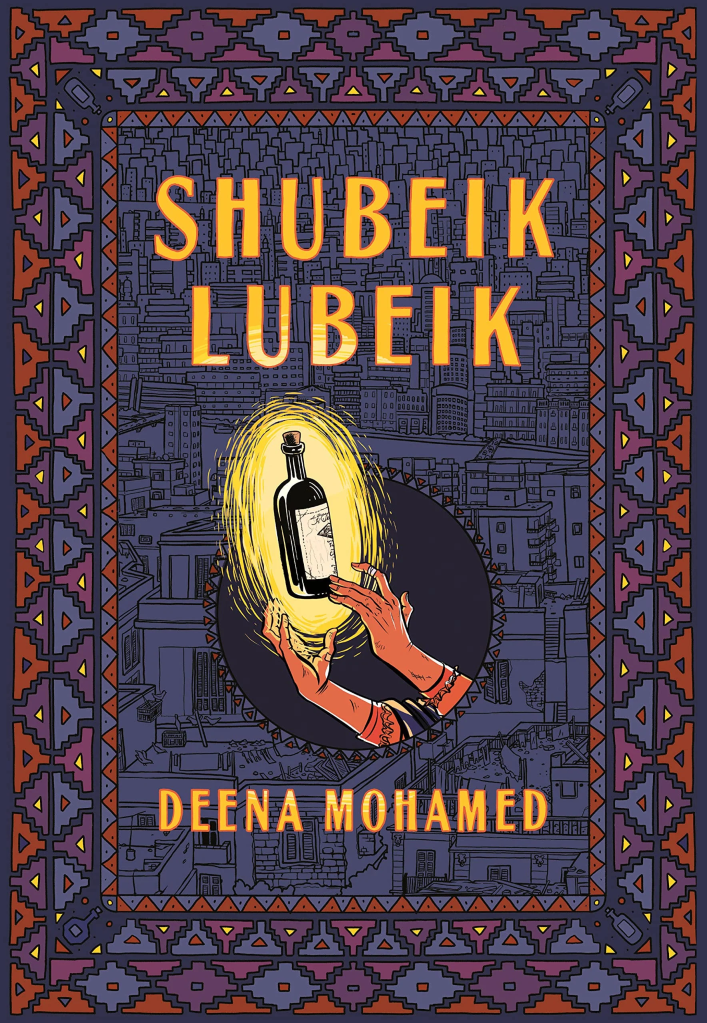

Wishes in lore tend to be unreliable things, at best limited to a certain number, but more likely bringing something undesirable, such as overly literal granting to the wish’s wording, Monkey’s Paw style. In Deena Mohamad’s Shubeik Lubeik, the temptation and calculus of wishing gets more complex with the different dimensions of each wisher’s life.

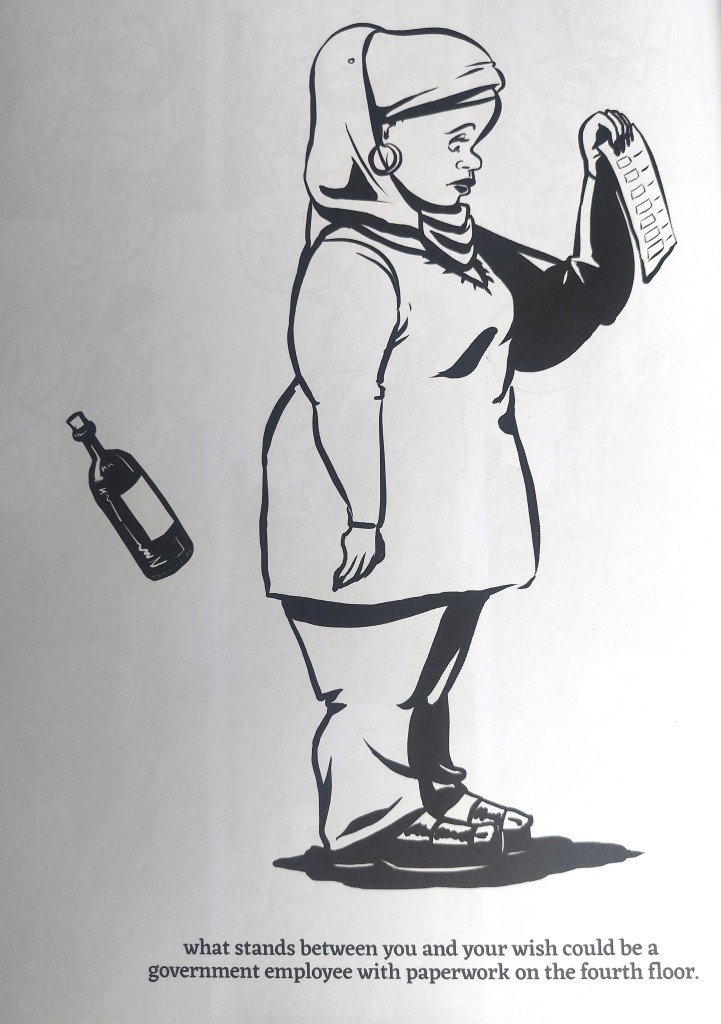

Wishes tend to come in threes, and that holds with Shubeik Lubeik (which translates, more or less, to “Your wish is my command”), in which people around the world can purchase wishes that have been mined and bottled, according to the quality of the wish. Each of the graphic novel’s three sections focuses on a different wish made from a set of three top-tier bottled wishes. These wishes are expensive and rare, but after the death of her husband from a third-rate wish, Aziza works long and hard to save up to buy one. People like Aziza don’t usually get first-rate wishes, though, and when she tries to follow the law and register this first-rate wish, she is arrested and indefinitely held, ostensibly out of (unfounded) suspicion about how she came to have such a valuable item.

Meanwhile, the people in Nour’s ritzy neighborhood don’t bother registering their many wishes—if they can afford to feed their dinosaurs, they can afford the fine they’d get if they were caught breaking wish law—but despite the comfortable circumstances Nour has in his home and college, he feels like he’s drowning. Knowing how much better he has it than others only makes him feel worse. He buys a first-rate wish on a whim and carries it with him, certain he can solve his emotional problems with a perfectly worded wish. The more he thinks and talks with others, the more he realizes poor mental health isn’t hte sort of thing you can just wish away. But this is a foreign concept to his friends, family, and others in this world of instant gratification.

Shokry, a second-generation shopkeeper, has seen the unhappiness that has come to his only two wish customers—imprisoned Aziza and depressed Nour—and knows his father was right about the wishes being curses. His father forbade anyone in the family from using the three first-rate wishes, or from selling them, and Shokry regrets not heeding his father’s advice, even though his shops are in dire financial straits and the sales from the two wishes have kept him afloat. He wants to be rid of the final wish, and a sick friend seems to be the perfect recipient for a gift like a first-rate wish—if only she would accept it. Faith, love, and worry wrestle in Shokry as she gets closer to death and Shokry reflects on the ramifications of wishes and the industry supporting them.

The characters and stories in each of these sections are as diverse as the reimagined Egypt they inhabit. Mohamad’s vision of wishes so quickly and thoroughly colonized and corporatized is uncomfortable because of close to the truth it probably would be. The kind of cheap (accessible) wishes that killed Aziza’s husband have been outlawed, but market demands means they’re about as easy to get as a lotto ticket, and about as likely to change the purchaser’s life for the better. The repercussions from wishes are negligible for the haves and devastating for the have-nots. Following the rules is detrimental for some, and far outside the sphere of concern for others. As with many things designed to “make life better”—technology, say, or medicine—the artificial scaffolding around wishes exacerbate, rather than reduce, inequality in the society they occupy.

That inequality is shown perhaps most clearly in the gulf between Aziza and Nour. Although they never meet, the placement of their stories one after another, and how different their lives are despite being in close enough proximity to frequent the same shop, is dizzying. The injustice in Aziza’s story is haunting; Nour’s struggle with the severity of his mental health compared to the real suffering of people like Aziza is uncomfortable and relatable. Nour’s story is heartbreaking in its own right, and I’ve recommended it specifically to someone who has been thinking a lot about mental health himself, but it never quite escapes the shadow of its predecessor.

Rounding out the book comes Shokry’s perspective, which is so self-reflective that it initially felt like a letdown by comparison. Shokry is pulled between what he’s believed his whole life about wishes, as told to him by his father and his religious leaders, and validated by so much of the wish-related chaos he’s seen, and someone close to him suffering in a way he knows a wish could solve. Conversely, his assumption that most people want to solve their problems with wishes is challenged by his friend’s staunch refusal, despite him and her family all begging her to take the offered wish and live longer. (Her story, when it finally unfolds, is one of the most touching moments in the book, and I know I’m going to be thinking about it for a long time.)

If Aziza’s story highlights inequality between classes and within bureaucracy, and Nour’s explores how no amount of a charmed existence can erase mental illness, Shokry’s story is familiar as an older person whose fervent beliefs against an idea falter when the idea suddenly becomes personal. Wishes in stories aren’t new, and neither are any of the problems the characters in Shubeik Lubeik face. It’s also timely, and timeless. Somehow, all of it feels fresh and bare when the promise of change is, or could be, or should be, just a wish away.