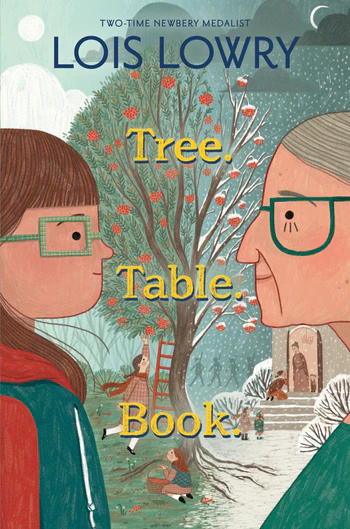

It took a while in Lois Lowry’s latest middle-grade novel, Tree. Table. Book., for me to understand the title. When I did, I thought I knew exactly what kind of crushing ending I was heading towards.

I was wrong, but the conclusion that Lowry weaves out of the threads of a precocious eleven-year-old and her 88-year-old best friend is far more heartwarming, complex, and, yes, heartbreaking than I could have imagined.

Sophie Winslow and Sophie Gershowitz might seem like a funny pair, but the two Sophies, besides being next-door neighbors, are kindred spirits in present-day New Hampshire. The younger Sophie goes over every day to talk to her friend, help with little things around the house, and play with her cat, the aptly named Mr. Katz. But the summer Sophie turns eleven, she overhears her parents talking about the older Sophie’s son coming to get her screened for dementia and probably put her in an assisted living facility in Ohio.

Fortunately for both Sophies, the younger girl is full of great ideas. Another neighbor, Ralph, has a doctor for a father, and Sophie asks if she can borrow his father’s copy of the Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy. This way, she decides, she can help the older Sophie study for, and pass, the dementia screening test. But as the younger Sophie works with the older woman to sharpen her memory, she gets more than she bargained for. The older Sophie’s short-term memory might be failing, but her recollections of her past—especially her distant past—are crystal clear, and the younger Sophie realizes there’s much more to her friend than she realized.

My first exposure to Lowry’s work was Number the Stars, her 1989 novel I got as a gift one Christmas. Always a voracious reader but never one to be told what to read, I dragged my feet, only to be swept away within only a few pages of the WWII story. I would have found The Giver and its sequels in my school library about that time, too, and was rocked in a completely different way. Over her career, Lowry has written more than fifty books, and it’s always amazed me how different each that I have read has been. I think, though, this was the first of her books I have read as an adult—certainly the first I have read for the first time. I kept pausing to consider how my child self would have reacted to the story, wondering how much and when she would have caught onto the subtext.

The younger Sophie’s determination to keep her friend in her home is palpable, though Lowry also shows us all the reasons the older Sophie would perhaps be better off living closer, at least, to her son. Little slips of the memory, mostly, though forgetting the tea kettle on the hot stove, for example, is more dangerous than forgetting what day of the week it is. A Jewish, Polish-born woman who speaks little and cryptically about her past and is pushing ninety in a story set in the present? There are certain inferences that can be easily drawn from that, as well, though the younger Sophie has no way of putting those particular pieces together. When she does, the reality crashes up against her notion of the world.

“I get As in history always,” she says. “I memorize the dates and the names of the battles, but…those things aren’t enough. You can’t feel them. You need the stories.”

It’s a pivotal moment in adolescence, the first peeling-back of the world and seeing the complexity where you thought there was only black and white. (One hopes it waits until adolescence, and that it comes at all.) It’s a hard moment for the younger Sophie, and the elder Sophie has her own hard moments at present, and in the near future. Yet what does remain simple is the beauty of their unconventional friendship, and how common ground can erase years and miles and practically an entire life between them. Tree. Table. Book. is a reminder of the pain of life and the beauty that can come after, and how that cycle of the good and bad is in a way the loops that knit a life together.