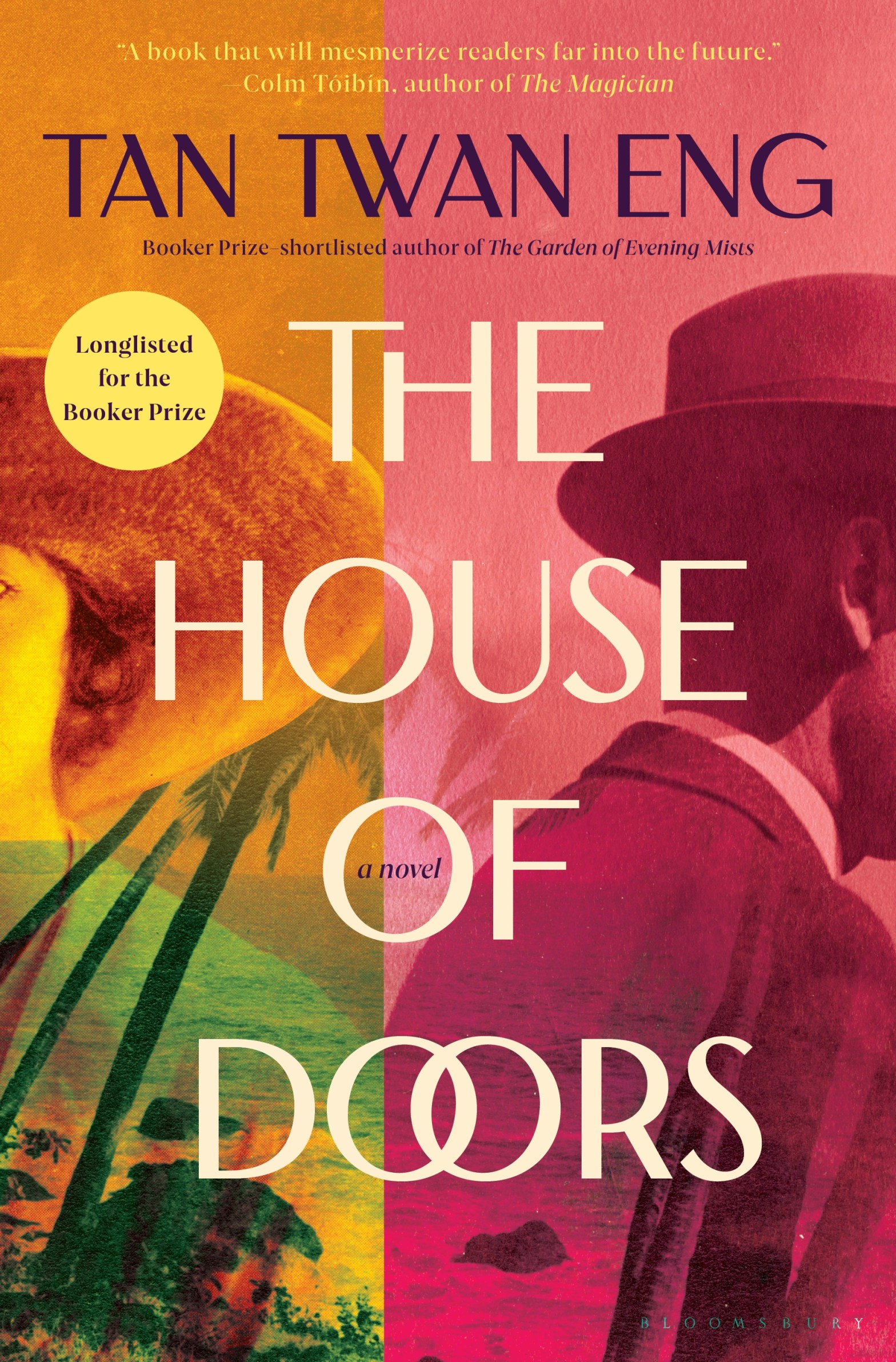

The art of storytelling is fraught with the inherent truth that any telling, no matter how hard its teller tries to be accurate and comprehensive, will always carry some slant of the events, some fault of memory or color that the teller may or may not intend to give it. The more tellers a story passes through, the greater this distortion becomes. That truth is a bright throughline in Tan Twan Eng’s The House of Doors.

In 1921 Malaysia, Lesley Hamlyn and her somewhat older husband, Robert, live in a charmed house and enjoy receiving visitors—such as the famed writer Willie Somerset Maugham. Willie and Robert served together during the Great War, both fighting for England, and are enjoying the opportunity to catch up, even as Robert’s health declines from an old war injury. But it’s Lesley with whom Willie finds himself particularly interested. Not for any romantic reasons—his “secretary” Gerald is fulfilling that particular need—but because Willie needs a new hit and fast, and Lesley has quite a story to tell.

Eleven years before, a killing of a white man by a white woman rocked the country—among the Asian population because white people were not charged with crimes, let alone convicted of them, let alone a woman; and among the European population because the crime, either cold-blooded murder or self-defense after the man supposedly attempted to assault the woman, challenged their long-held belief that they were inherently superior to the local population. Lesley had a personal interest in the case: the accused was a personal friend. Meanwhile, a burgeoning Chinese revolution was staging itself, creating even more excitement, and tension, in the city. Lesley is an open book, so to speak, confessing even her fears of Robert having an affair.

Willie’s work might be a critical and commercial hit, but it’s also true that he tends to draw heavily on real life…without, perhaps, always shielding the true identities of those whose stories he’s “borrowed.” But Lesley keeps talking, and Willie keeps listening, and writing.

There are a lot of themes in play in The House of Doors, not least among them racism, classism, sexism, and colonialism. The Hamlyns live in positions of privilege, even by the standards of their European expat peers. Lesley wields that privilege when she can, but she’s also a victim to other standards; she has to be a little sneaky with her volunteering with the revolutionaries lest she upset Robert, and accepting a fellow volunteer’s invitation to see his collection of painted doors is no simple thing, given the implications if the wrong person sees a white, married woman alone with a Chinese man. In these years of suffragettism, her comfort asserting herself might be more modern than authentic, but it illustrates well her struggle against the constraints of the surrounding society. And no matter how much Lesley tries to treat all those around her equally, there is no perfect equality under empire—a fact made evident twice over.

The House of Doors is slow—literary, we’ll say—despite the murder and adultery and revolution sprinkled throughout its pages. There are three timelines woven together here, and, though they are delineated clearly and one is present only at the beginning and end, building essentially three stories takes time. The second act, in particular, lacked the propulsion I was expecting, and, looking at the stack of other books on my TBR, I almost set this one aside. I’m glad I didn’t. Once the pieces start falling into place, the story reveals itself to be a curious story more about connection than the events at hand. What initially seems like naivety or secondhand confessional turns out to be something far lovelier, and more than worth the time it takes to get there.